Dear Catalysis Researchers,

Welcome to our monthly newsletter Magic Powder dedicated to the catalysis research and development.

In this monthly issue, we present a detailed article about Uzun Lab led Professor Alper Uzun, at Koç University (Page 2) and a brief discussion on biocatalytic fuel cells by Prof. Dr. N. Alper Tapan in our new scientific column “Catalysis is Everywhere” (Page 9). In addition, you can see short summaries of most recent high impact research articles conducted by Turkish Catalysis Community (Page 11).

Thank you for being part of our catalysis community. We look forward to bringing you more exciting updates in the next edition of our newsletter. We are always open to contributions of academic and industrial partners in our upcoming issues.

In this monthly issue we did not forget to challenge you with our puzzle from Professor Merlin Catalystorius 😊.

Editorial Board:

Prof. Dr. Ayşe Nilgün AKIN

Prof. Dr. N. Alper TAPAN

Dr. Merve Doğan Özcan

Contact info:

Email:katalizdernegi@gmail.com

Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/kataliz-derneği-272879a

Uzun Lab.

The Uzun Lab, led by Professor Alper Uzun, at Koç University, is dedicated to addressing future energy challenges. Our primary focus lies in developing materials for two key areas: i) converting hydrocarbons into valuable fuels and ii) the storage and separation of gases. In this regard, our methodology centers on the precise synthesis of materials coupled with thorough characterization, complemented by precise experimentation to determine various performance metrics. We then analyze any variations in performance measures based on the structural differences to reach a fundamental-level understanding on the structure-performance relationships. Leveraging this insight, we innovate novel materials with superior performance characteristics.

Thorough characterization is a crucial component of our research. Our lab is well-equipped to accomplish this objective. The infrared spectrometer with in situ capabilities, the temperature programmed desorption/reduction/oxidation/reaction and chemisorption equipment, and the thermogravimetric analyzer are some of the key equipment driving our efforts in this regard. Besides, our group has direct access to the state-of-art characterization facilities available at Koç University. Any sample synthesized by our group undergoes thorough characterization by combining many of the advanced characterization tools, such as X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy and atomic resolution aberration-corrected scanning transmission electron microscopy. On top, we utilize beamtime at Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL), a division of SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, operated by Stanford University to perform synchrotron-based X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) to be able to characterize our catalysts under operando conditions. Combining the power of all these tools provides us with an opportunity to resolve the structure of our catalysts at the atomic level, even under operating conditions.

Such detailed information on the structure is then used to elucidate the structure-performance relationships. Our flow reactor systems are capable of real-time monitoring of effluent streams by means of online gas chromographs and mass spectrometers. We adjust space velocities and partial pressures of the reactants under kinetically relevant conditions to fully understand the catalytic behavior of our catalysts. These measurements, most of the time, are coupled with in situ and ex situ characterization to identify any structural changes occurring on our catalysts in the working state. “Rigor” is our top priority for all these measurements. If needed, we also utilize our batch reactors as well. Extending from continuous flow reactors to batch reactors, we can measure the catalytic performance of our catalysts under a wide range of conditions, spanning from atmospheric pressure to pressures up to 200 bar, and temperatures reaching 1200 °C.

Scheme 1: Cover arts from the group

Our projects cover a wide spectrum, from fundamentals to industrial applications, and always target the prestigious journals of the field (Scheme 1). For example, we work on overcoming the challenges associated with the atomically dispersed supported metal catalysts. In this regard, we coat them with ionic liquids (ILs) to investigate the structural factors controlling the performance of IL-coated supported metal catalysts and use special supports, such as graphene aerogel (GA) reduced at different conditions, zeolites, and metal organic frameworks to control the surface electronic structure. We collaborate with Dr. Simon Bare of SSRL, Prof. Bruce Gates of UC Davis, Prof. Viktorya Aviyente and Prof. Ramazan Yıldırım of Boğaziçi University, Prof. Uğur Ünal and Prof. Seda Keskin of Koç University for these research efforts. We also work on supported metal nanoparticles and investigate the relationships between the surface characteristics of supports and the active sites located at different positions on the supported metal nanoparticles. These efforts also cover a reaction crucial for hydrogen economy: ammonia decomposition. We use ammonia as a hydrogen storage molecule and work on developing cheap catalysts capable of efficiently decomposing it to produce hydrogen. Our research also includes industrial applications with special focus on converting gaseous hydrocarbons into liquid fuels. We have been collaborating with industry for more than a decade to direct these efforts. For instance, we worked on developing selective catalysts for the conversion light olefins into liquid fuels and green fuel additives. Our long-lasting collaboration with industry now continues with a project focusing on the conversion of CO2 into liquid fuels. These efforts not only shed light into major energy related problems, but also provide broad opportunities for the members of our group to prepare themselves for the industry. As an excellent proof of this, we had several graduates appointed as research engineers/scientists at the R&D center of our collaborators from the industry. Besides these research efforts on catalysis, we also collaborate with Prof. Seda Keskin’s Group at Koç University to diversify our research focus with materials for gas storage and separation applications. In this regard, we apply post-synthesis modifications on porous materials to boost their gas storage and separation performance. Following is a brief overview on some of the projects we have been working on:

Atomically dispersed supported metal catalysts

One of the emerging topics in the field of heterogenous catalysis is the atomically dispersed supported metal catalysts. In these novel catalysts, noble metals are present as site-isolated active species anchored onto supports, offering a maximum possible metal dispersion of 100%. As a result, they offer the best possible utilization of expensive transition metals with structures simple and uniform enough to allow decisive characterization for the investigation of structure-performance relationships. Even though there exists a tremendous interest on this topic, there is still very limited insights into overcoming the major challenges related with these novel catalysts: (i) tuning their catalytic performance, (ii) improving their stability, and (iii) enhancing their metal loadings. These challenges set the focus of our research on atomically dispersed supported metal catalysts:

Tuning the catalytic performance of atomically dispersed supported metals requires an ability to precisely control their electronic structures. In this regard, we work on i) modifying their ligation environment, including supports, ii) coating them with an IL layer, and iii) controllably adjusting their metal nuclearity, while still maintaining the atomic dispersion. For instance, we synthesized Ir(CO)2 complexes on various high-surface-area metal oxides with increasing electron-donor strength. Spectroscopy data indicated that electron density on iridium centers increases with support’s electron-donor strength. Subsequently, results of catalytic performance tests presented a strong correlation between the electron density of iridium sites and their selectivity towards partial hydrogenation of 1,3-butadiene (Chem. Sci. 2019, 10, 2623).

Another way of changing the electronic structure on an active metal center is to vary its nuclearity by forming metal clusters, which are small enough to offer 100% metal dispersion. For example, recently we demonstrated the transformation of atomically dispersed graphene aerogel-supported iridium complexes into Ir4 and Ir6 clusters as a response to changes in both temperature and reactant composition during ethylene hydrogenation. Comparison of the turnover frequencies indicated a more than two-order-of-magnitude boost in performance with increasing metal nuclearity (J. Catal. 2022, 413, 603).

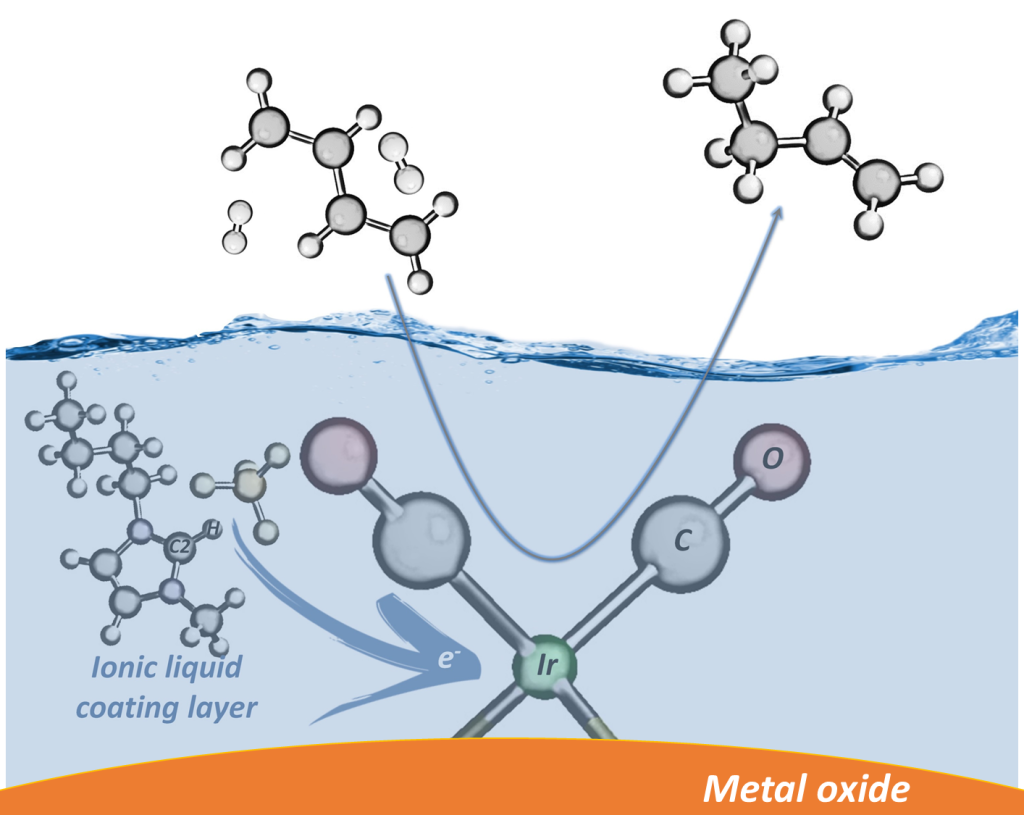

These examples show that one can tune the catalytic performance of an atomically dispersed supported metal complex by either changing the support or by controlling the metal nuclearity. However, these approaches are limited. Because it might not be possible to maintain atomic dispersion on every support, or metal aggregation might go beyond small clusters and form large nanoparticles. In this regard, our group is among the pioneers of a novel approach, which offers a highly flexible route for controlling the electronic structure of active metal centers by coating them with a very thin layer of an IL (Scheme 2). These coating materials are salts, which are mostly liquid below 100 °C, and offer almost limitless number of structural possibilities. When they are in contact with active metal centers, they can either work as a macro-sized ligand to adjust metal’s electronic structure or as a selective layer to control effective concentrations of reactants/intermediates/products. For instance, in a groundbreaking study, we demonstrated that the electron density of atomically dispersed Ir(CO)2 complexes supported on -Al2O3 can be directly tuned by coating them with a thin layer of IL (ACS Catal. 2017, 7, 6969). Spectroscopy data showed that the IL donates electrons to the metal site and that the degree of electron donation increases with an increase in interionic interaction energy. Catalytic performance measurements complemented these results and demonstrated a strong correlation between the selectivity for butenes during 1,3-butadiene partial hydrogenation and the electron density on iridium. In a follow up study, we presented that the ligand effect of ionic liquid layer becomes more dominant as the electron-donor strength of the support becomes weaker. Hence, catalytic performance of atomically dispersed supported metal complexes can be tuned by the synergistic interplay between the IL layer and the support enveloping the active species, both of which act as macro-sized ligands. Next, we investigated the relative strengths of these ligand effects as a function of metal nuclearity. We prepared iridium complexes and clusters on three different supports with varying electron-donor characters and coated them with IL again with varying electron-donor characters. Our data demonstrated that ligand effect of ILs become more dominant when the metal nuclearity is high; whereas the ligand effect of support becomes more dominant as the metal nuclearity decreases. All these results demonstrate the broad opportunities for tuning catalytic performance by the selection of IL coating layer-support combination, and the importance of making this selection based on the metal nuclearity (J. Catal. 2020, 387, 186).

Scheme 2:Enveloping atomically dispersed iridium catalyst with supports and IL coatings.

Another major challenge associated with atomically dispersed supported metal catalysts is to keep them stable in reactive conditions. In this regard, our research focuses on elucidating the structural factors controlling the stability of atomically dispersed supported metal catalyst under various conditions.

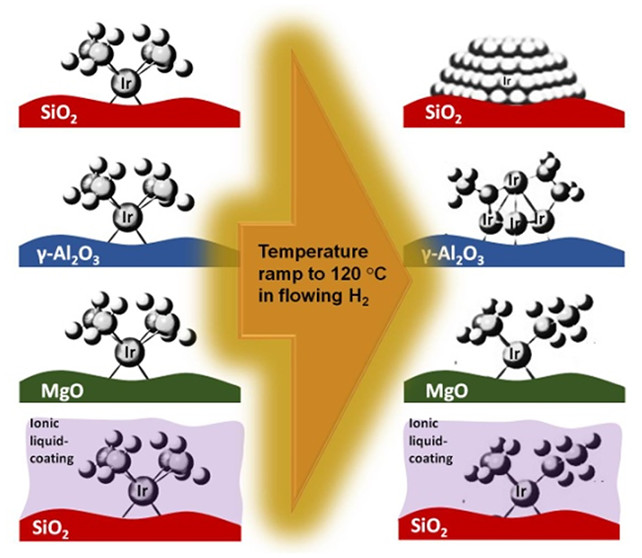

In this respect, our recent work illustrates how the stability can be tuned by adjusting the electron density on metal centers (as summarized in Figure 1). We prepared atomically dispersed Ir(C2H4)2 complexes on SiO2, γ-Al2O3, and MgO and treated them under flowing hydrogen as the temperature was increasing to 120 °C. During this treatment, we monitored the structural changes by X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS). Data demonstrated that treatment led to the formation of large nanoparticles when the support was weak-electron-donor (SiO2). However, as the electron-donor strength of the support increases to a moderate level (on γ-Al2O3), the level of iridium aggregation remained limited with the formation of small clusters. When the support was strong-electron-donor (MgO), on the other hand, data demonstrated the lack of any cluster formation. Next, we coated the iridium complexes supported on SiO2 with an electron-donor IL, 1-ethyl-3-methyl-imidazolium acetate ([EMIM][OAc]). XAS data collected during an identical treatment showed that electron donation from IL to iridium hindered iridium’s aggregation and helped in maintaining atomic dispersion (ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 12354). Complementing these results, our recent findings showed that the stability of a supported metal complex can be improved further with a change in its ligand environment as well (Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 485, 149738; J. Catal. 2024, 429, 115196).

Figure 1:Electronic structure controls iridium aggregation

Stability becomes even more challenging especially at high metal loadings. Motivated from the results with IL coatings as presented above, we employed a thin layer of [EMIM][OAc] on the rGA-supported Ir(C2H4)2 complexes and performed the identical treatment which led to Ir6 cluster formation on the uncoated counterparts under ethylene hydrogenation conditions (as discussed above). Our operando XAS data demonstrated that [EMIM][OAc] coating helped in maintaining the atomic dispersion even at an iridium loading of 9.9 wt%. These results illustrate the control of stability by tuning the electron density of active metal centers again by the rational selection of IL coating layer-support combination (ChemCatChem, 2022, 14, e202200553).

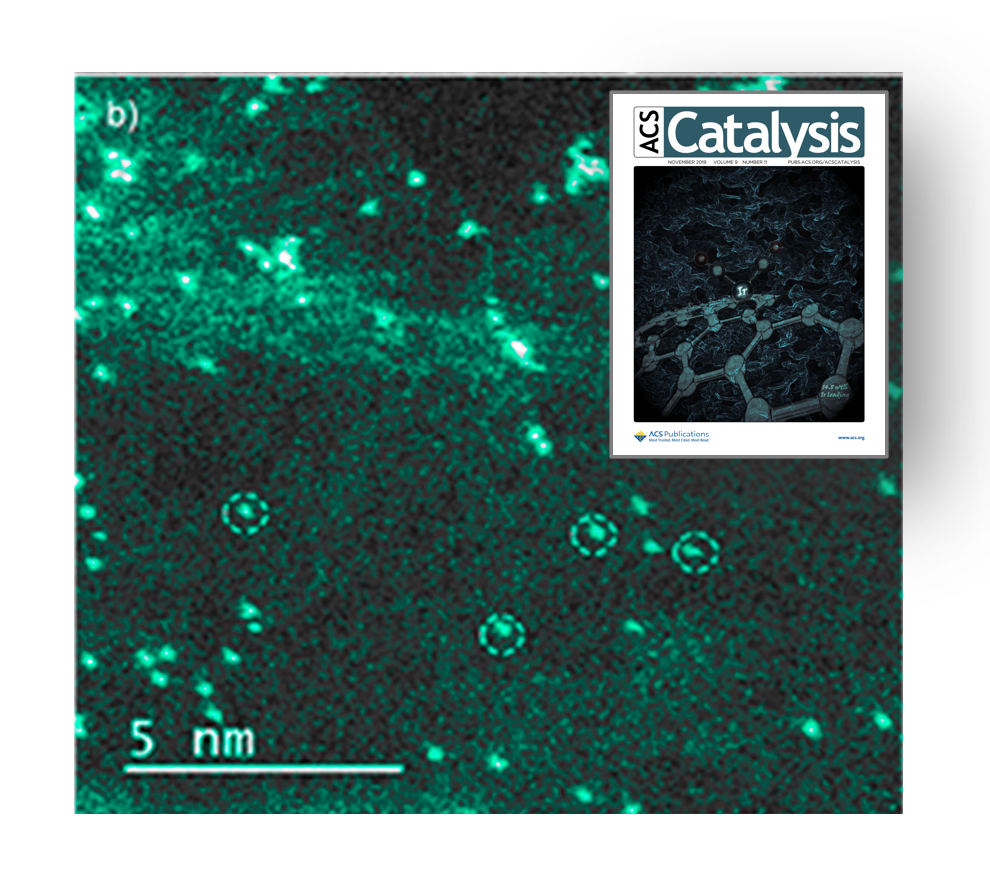

Metal loading in these novel catalysts is typically below 1 wt% to keep the active metal centers well-isolated. However, it is desired to maximize the active site density in a given reactor volume. This need is also linked to the limitations with stability as well. In this regard, we use a very special support, graphene aerogel. Owing to its exceptionally high surface area and high density of oxygen-containing functional groups available for anchoring metal complexes, we could reach an iridium loading of 15 wt% on an atomically dispersed supported Ir(CO)2 catalyst (Figure 2) (ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 9905). Later, we pushed the limits even further and increased the iridium loading to 25 wt%, in addition to replacing the relatively inactive carbonyl ligands with reactive ethylene ligands. Our operando XAS data showed that this graphene aerogel-supported Ir(C2H4)2 catalyst is stable under ethylene hydrogenation condition even at such a remarkably high iridium loading.

Figure 2: STEM evidence on atomic dispersion of graphene aerogel-supported Ir(CO)2 at an Ir loading of 14.8 wt%.

Supported metal catalysts for partial hydrogenation

Identifying the true active site on a catalyst is of paramount importance for the catalysis field. It becomes a major challenge when working on a conventional supported metal catalyst, where the transition metals are dispersed on support surfaces as nanoparticles of different sizes and shapes. Catalytic performance of the active metal centers located on the surface of these nanoparticles depends on many factors, such as the size and shape of the nanoparticles carrying these active sites, location of the active sites on these nanoparticles, and the electronic influence of the supports on these sites. Our research also focusses on the elucidation of these structural factors and their influence on the catalytic performance. For instance, in a recent work, we focused on a family of supported copper catalysts. Copper-based catalysts can offer a high selectivity for partial hydrogenation reactions. However, they tend to deactivate quickly because of coke formation; thus, they cannot compete with their much more expensive Pd-based counterparts. In this project, we synthesized a series of low-cost CunCeMgOx catalysts with various copper nanoparticle sizes and surface defect densities and tested them for partial hydrogenation of 1,3-butadiene. Among the catalysts considered, Cu0.5CeMgOx with the smallest copper nanoparticle size showed a complete selectivity to partial hydrogenation and an excellent stability at a comparably high performance to those of Pd-based catalysts even under harsh conditions. Detailed characterization complemented with kinetics analysis demonstrated that the preferred reaction pathway involves the dissociation of molecular hydrogen on the peripheral oxygen vacancies (Ov-Cu+) before reacting with 1,3-butadiene adsorbed on the corresponding Cu+ atoms. Our analysis revealed that the turnover frequency of these Cu+ sites is approximately five-times higher than those of the surface Cu0 sites. The analysis also indicated that coke formation occurring on the catalysts with relatively larger Cu nanoparticles is associated with the insufficient supply of dissociated hydrogen from the interface to the surface Cu0 sites. These findings offer a broad potential for the rational design of low-cost, highly selective, and stable partial hydrogenation catalysts for reactions that are prone to coke formation (ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 8116).

Materials for gas storage and separation applications

In addition to our research efforts on catalysis related projects, we also collaborate with Prof. Seda Keskin’s Group to work on developing novel hybrid materials with exceptionally high gas storage and separation performance under realistic operating conditions. Our aim here is to incorporate ILs into porous materials, mostly MOFs, to benefit from tunable physicochemical properties of ILs in improving the gas storage and separation performance of the host material. We combine experiments with molecular simulations to understand the effects of IL incorporation on the gas separation performance. We examine the interactions between ILs and host material in deep detail combining various experimental techniques and complement the findings with density functional theory (DFT) calculations. Then, we investigate the consequences of these interactions on gas storage and separation performance. Our findings illustrate that these interactions lead to enhanced gas selectivities especially at low pressure regime upon IL incorporation. Considering the adsorption is the very first step for any catalytic reactions, our expertise in catalysis is the key in developing these adsorbents with exceptional gas storage and separation performance. For instance, in a pioneering work by our collaboration, a novel material with exceptional CO2 separation performance was developed. We deposited a hydrophilic IL, 1-(2-hydroxyethyl)-3-methylimidazolium dicyanamide, [HEMIM][DCA], on a hydrophobic zeolitic imidazolate framework, ZIF-8, to form a powder composite. Characterization illustrated that the IL molecules were mostly present on the external surface of the MOF to form a core (MOF)-shell (IL) type material, where the IL acts as a smart gate controlling the selective transport of guest molecules such that it lets the CO2 molecules in, while rejecting the CH4 molecules and results in an exceptional CO2/CH4 selectivity (J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 10113).

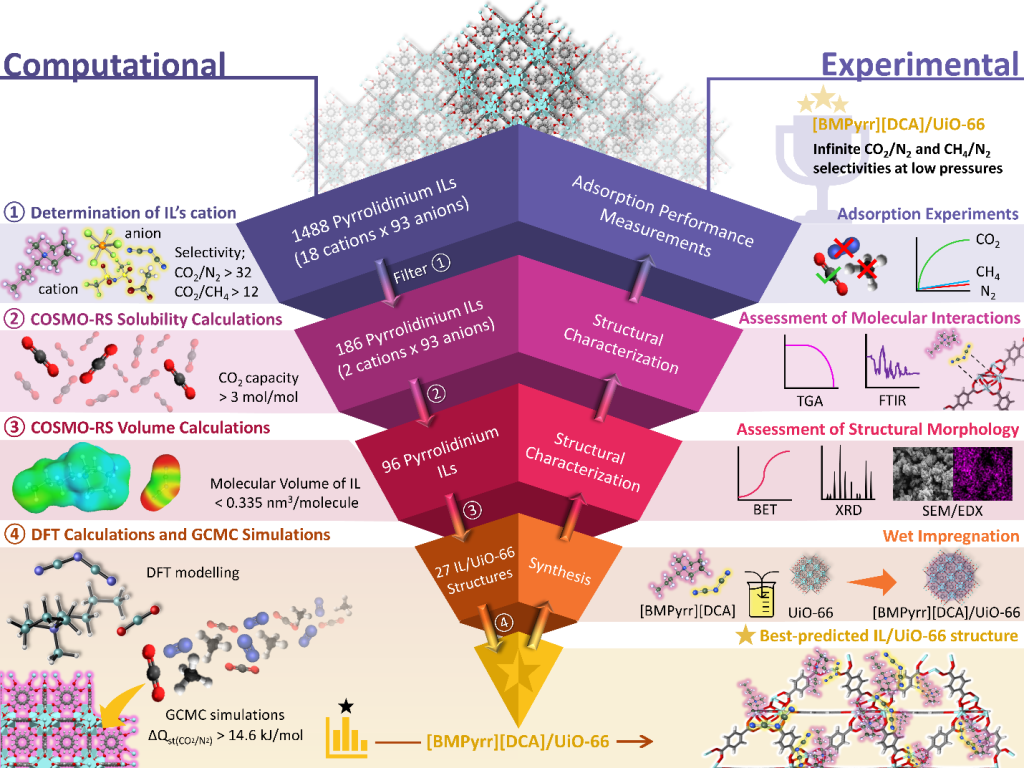

Theoretically unlimited number of possible IL-porous material combinations with tunable physicochemical properties offer tremendous potential in tuning the gas storage and separation properties of the host material. The molecular simulations can quickly screen many different combinations to guide our experimental studies. This approach (Scheme 3) provides significant advancements towards the rational design of new materials for meeting future energy challenges, as exemplified by a recent work where we demonstrated an integrated computational–experimental hierarchical approach for the rational design of IL/MOF composites. The best IL-MOF combination determined by screening thousands of different combinations offered practically infinite CO2 selectivity over N2 (Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2204149).

Scheme 3: An integrated computational–experimental hierarchical approach for the rational design of an IL/MOF composite

Materials for hydrogen energy

Another of the primary areas of focus for our group is hydrogen energy. To this end, we are affiliated with the recently established Koç University Hydrogen Technologies Center (KUHyTech). KUHyTech is dedicated to conducting both fundamental and translational research in new materials, structures, and systems for hydrogen energy and related technologies, addressing the three key pillars of hydrogen technologies: production, storage/separation, and utilization. This interdisciplinary center facilitates collaboration among faculty from various fields to generate cutting-edge research with direct implications for the energy industry and society at large; and hence, it aims to help bridge material/molecular level fundamental research with device/prototype level investigations. Our group's research aligns closely with these objectives. Like other groups affiliated with the center, we are excited about the forthcoming state-of-the-art research facilities and the generous scholarship opportunities offered by KUHyTech.

Last but not least

For any research group, success depends on these dedication of its members to excellence in research. In this regard, our group considers itself fortunate to have teammates who excel not only in research but also in their personal qualities. Their exceptional traits and commitment to research excellence have fostered an ideal research environment. To sustain this, our group is currently seeking new members, offering multiple positions at the MS, PhD, and post-doctoral levels. We are confident in providing our members with the best research opportunities, supported by competitive scholarships from KUHyTech and Koç University. There has never been a better time to join us. Please contact auzun@ku.edu.tr to discuss possible opportunities to join the Uzun Lab or visit https://kuhytech.ku.edu.tr/ to connect with the outstanding faculty members affiliated with KUHyTech, who are also looking for high caliber researchers for their esteemed research groups.

Link to our GoogleScholar page:

https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=esFM64IAAAAJ&hl=en

CATALYSIS IS EVERYWHERE

Biocatalytic Fuel Cells in Brief

By

Prof. Dr. N.Alper TAPAN

Day by day, medical advances bring miniaturized devices which can be implanted into the human body. Considering that these devices use existing battery technology for their energy sources, we can predict that using reactive alkali metals such as lithium and corrosive electrolytes in batteries will be quite problematic in biological systems. If fuel cells are considered as an alternative to the existing secondary batteries, the use of enzymatic catalysts is in question. In addition, as an available fuel source, glucose, which is abundant in biological systems (which is around 9 mM in the blood), was used in these systems (composed of platinum electrodes and ion exchange membrane), which date back to 1964 [2]. Apart from glucose, molecules such as alcohols, lactate, fructose, and sucrose can also be considered as fuel sources [1]. Biocatalytic fuel cells, which have an advantage in terms of design simplicity compared to batteries, seem to have a long way to go in electrocatalyst design. The problematic electron transfer efficiency, especially after the breakdown of glucose by glucose oxidase at the anode or during oxygen reduction at the cathode, requires the mediation of enzyme catalysts. Hinderence of the active site (Flavin Adenine Dinucleotide (FAD)) under a thick protein layer (15Å) of the glucose oxidase enzyme, which is inevitable for the breakdown of glucose, is one of the most important factors affecting the electron transfer efficiency at the anode electrode [3]. Therefore, different approaches are being developed to increase electron transfer from FAD. Examples of these include direct attachment of the FAD active center to the electrode surface and subsequent placement of the protein layer, wiring of the enzyme to the electrode surface with polymer chains containing osmium complex electron carriers (relays), using osmium relays with carbon nanotubes or using mediators such as ferrocene [4,5,6,7]. Therefore, thanks to such research works which lead to increase in the electron transfer rate in bioelectrocatalytic systems. While performing these electrocatalytic studies, the limitations of thermodynamics stand out. For example, in a bioelectrocatalytic fuel cell, which is a galvanic system where glucose-enzyme and mediator are present, the order of standard potentials must be Εoglucose<Eoenzyme<Eomedium in order for the breakdown of glucose and electrons to be transferred to the mediator during glucose oxidation [1]. In these bioelectrocatalytic systems, in addition to enzyme modifications, enzymes like iron-containing peroxidase and copper-containing laccase [8,9], which consist of amino acid chains and metal complex structures, are used to increase the efficiency of the oxygen or hydrogen peroxide reduction reaction and to reduce the reduction overvoltage at the cathode. In addition, glucose dehydrogenase is used instead of glucose oxidase to prevent oxygen consumption during glucose breakdown at the anode [10]. Therefore, this brief discussion indicates that enormous possibilities exist in catalytic studies to develop biocatalytic fuel cells, which will open new perspectives in monitoring, diagnosing, and curing medical conditions. The following resources below can be used for further reading.

[1] D. Leech, M. Pellissier, and F. Barrière (2011). Powering fuel cells through biocatalysis. In Zhang, X., Ju, H., & Wang, J. (Eds.), Electrochemical sensors, biosensors and their biomedical applications (pp. 385-410).

[2] A.T. Yahiro, S.M. Lee, and D.O. Kimble, Biochim. Biophys. Acta 88, 375 (1964).

[3] Mano, N. (2019). Engineering glucose oxidase for bioelectrochemical applications. Bioelectrochemistry, 128, 218-240.

[4] Willner, I., Heleg-Shabtai, V., Blonder, R., Katz, E., Tao, G., Bückmann, A. F., & Heller, A. (1996). Electrical wiring of glucose oxidase by reconstitution of FAD-modified monolayers assembled onto Au-electrodes. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 118(42), 10321-10322.

[5] Y. Degani and A. Heller, Direct electrical communication between chemically modifi ed enzymes and metal electrodes. I. Electron transfer from glucose oxidase to metal electrodes via electron relays, bound covalently to the enzyme. J. Phys. Chem. 91, 1285–1289 (1987).

[6]Kim, S. J., Quan, Y., Ha, E., & Shin, W. (2021). Enhancement of Electrocatalytic Activity upon the Addition of Single Wall Carbon Nanotube to the Redox-hydrogel-based Glucose Sensor. Journal of Electrochemical Science and Technology, 12(1), 33-37.

[7]Radomski, J., Vieira, L., & Sieber, V. (2023). Bioelectrochemical synthesis of gluconate by glucose oxidase immobilized in a ferrocene based redox hydrogel. Bioelectrochemistry, 151, 108398.

[8]Scodeller, P., Carballo, R., Szamocki, R., Levin, L., Forchiassin, F., & Calvo, E. J. (2010). Layer-by-layer self-assembled osmium polymer-mediated laccase oxygen cathodes for biofuel cells: the role of hydrogen peroxide. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 132(32), 11132-11140.

[9]Ramanavicius, A., Kausaite, A., & Ramanaviciene, A. (2005). Biofuel cell based on direct bioelectrocatalysis. Biosensors and Bioelectronics, 20(10), 1962-1967.

[10] Stolarczyk, K., Rogalski, J., & Bilewicz, R. (2020). NAD (P)-dependent glucose dehydrogenase: Applications for biosensors, bioelectrodes, and biofuel cells. Bioelectrochemistry, 135, 107574.

Recent Selected Papers in our Catalysis Community

In recent months, there have been exciting research studies in catalysis research in Turkey. Here are the short summaries:

Ammonia Synthesis

Kucuk, E., Koybasi, H. H., & Avci, A. K. (2024). Beyond equilibrium ammonia synthesis in a membrane and heat exchange integrated microreactor: A modeling study. Fuel, 357, 129858.

Ammonia synthesis was modeled in a micro-structured membrane reactor (MR) that integrates reaction, cooling, and NH3 separation functions in one unit, utilizing a zirconia supported ZnCl2 immobilized molten-salt (IMS) membrane selective to NH3 transport. The MR features reaction channels with an iron-based catalyst for H2 + N2 feed and permeate channels using N2 as a sweep gas to regulate temperature. Under specific operating conditions, the MR achieved approximately 47% N2 conversion, surpassing thermodynamic and membraneless cases, with operability maintained below the thermal stability limit of 623 K despite exothermic heat release.

Fine chemical synthesis catalysts

Buldurun, K., Turan, N., Altun, A., Çolak, N., & Özdemir, İ. (2024). Synthesis, Characterization and Catalytic Activities of Some Schiff Base Ligands and Pd (II) Complexes Containing Substituted Groups. Journal of Molecular Structure, 138185.

New Schiff bases (L1, L2) and their corresponding Pd(II) complexes were synthesized and characterized using various analytical methods. The L1-Pd(II) and L2-Pd(II) complexes exhibited catalytic activity in Suzuki-Miyaura and Mizoroki-Heck C-C coupling reactions, highlighting their versatility as effective catalysts for synthesizing sensitive and fine chemicals under mild conditions. This study demonstrates the potential of palladium complexes based on Schiff base ligands for a wide range of catalytic reactions.

Bensalah, D., Mansour, L., Sauthier, M., GÜRBÜZ, N., Özdemir, I., Gatri, R., & Hamdi, N. (2024). An efficient palladium catalyzed mizoroki-heck cross-coupling in water: synthesis, characterization and catalytic activities. Polyhedron, 254, 116932.

PEPPSI-type palladium complexes (3) were synthesized by reacting benzimidazolium salts (2a-e), potassium carbonate, and palladium chloride in pyridine. The resulting complexes and benzimidazolium salts were characterized using spectroscopic methods and elemental analysis. These complexes demonstrated high catalytic activity in Mizoroki-Heck coupling reactions in water under aerobic conditions, achieving excellent yields with a turnover frequency ranging from 12 to 14 per hour for various aryl bromides and chlorides.

Hydrogenation catalysts

Zhao, Y., Kurtoğlu-Öztulum, S. F., Hoffman, A. S., Hong, J., Perez-Aguilar, J. E., Bare, S. R., & Uzun, A. (2024). Acetylene ligands stabilize atomically dispersed supported rhodium complexes under harsh conditions. Chemical Engineering Journal, 149738.

Sintering of atomically dispersed noble metal catalysts at high temperatures under reducing conditions challenges their practical use, with carbonyl ligands stabilizing them but suppressing catalytic activity. Substituting carbonyl ligands with reactive acetylene ligands maintains atomic dispersion of the supported rhodium complex at temperatures above 573 K, as confirmed by in-situ XANES and EXAFS spectroscopies, while carbonyl-based complexes aggregate into nanoclusters under the same conditions. Acetylene ligands offer anti-sintering capabilities without compromising hydrogenation activity.

Machine Learning in Catalysis

Özsoysal, S., Oral, B., & Yildirim, R. (2024). Analysis of photocatalytic CO2 reduction over MOFs using machine learning. Journal of Materials Chemistry A.

Photocatalytic CO2 reduction over metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) was analyzed using a database and machine learning tools to predict total gas product yield and predominant product types. The random forest regression model achieved high predictive power with optimized hyperparameters, showing R2 values of 0.96 for training, 0.94 for validation, and 0.60 for testing. Reactor volume, sacrificial agent, and catalyst amount were crucial variables for predicting total gas production rate, while decision tree models accurately determined predominant product types in both gas-phase (87% accuracy) and liquid-phase (77% accuracy) systems based on photocatalyst properties and reaction conditions.

Photocatalysis

Ebrahimi, E., Irfan, M., Kocak, Y., Rostas, A. M., Erdem, E., & Ozensoy, E. (2024). Origins of the Photocatalytic NOx Oxidation and Storage Selectivity of Mixed Metal Oxide Photocatalysts: Prevalence of Electron-Mediated Routes, Surface Area, and Basicity. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C.

MgO, CaO, SrO, or BaO-promoted TiO2/Al2O3 was employed for photocatalytic NOx oxidation and storage, with performance influenced by catalyst formulation, calcination temperature, and humidity. Photocatalytic activity initiates with the transition from anatase to rutile phase in TiO2/Al2O3, increasing paramagnetic active centers and oxygen vacancies, while disordered AlOx domains enhance oxygen vacancies and paramagnetic centers, hindering titania particle growth and increasing specific surface area for oxidized NOx storage. The photocatalytic NO conversion involves both electron and hole-mediated pathways; 7.0Ti/Al-700 showed superior NOx storage selectivity due to trapped electrons at oxygen vacancies and a large specific surface area, with longevity enhanced by CaO incorporation, emphasizing surface basicity importance.

Upcoming Catalysis Events

126 days left to 7th Anatolian School of Catalysis (Date: 01-05/09/2024)

Don’t forget to register and check out updated web page below!!

Sponsored by European Federation of Catalysis (EFCATS)!!

Web site: https://meetinghand.com/e/7th-anatolian-school-of-catalysis-asc-7/

The 35th National Chemistry Congress with special session on Catalysis (Date: 09-12/09/2024)

Web site: https://kimya2024.com/

Don't miss out! Register now for these events and be part of the catalysis community.

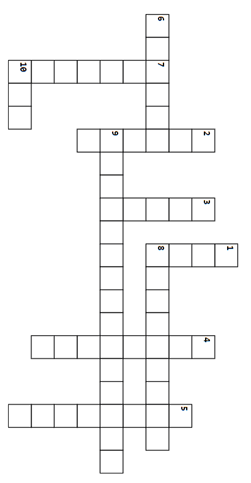

Down

6. Abreviation of technique where the infrared light produced by the sample's rough surface reflection in all directions is collected by use of an ellipsoid or paraboloid mirror

8. Abreviation of synthetic fuel laboratory built in Boğaziçi University

9. catalytic cycle where catalyst recovers its original oxidation state

10. abreviation for a class of three dimensional structures consisting of metal clusters

Across

1. Abreviation for the type of reaction which plays a pivotal role for CO2 utilization and syngas production

2. Abbreviation of synchroton light source in Middle East, Amman

3. Abbreviation of Turkish X-ray beam line in Amman

4. elastic scatering of light by particles

5. In the period after 1962, these catalysts dominated petroleum refining processes like hydrocracking of heavy petroleum distillates

7. Its complexes are used in photocatalysis

Last months’s puzzle

5.ACCEPTOR able to bind to or accept an electron or other species.

1.BIOCATALYST what laccase is

7.CRACKER where lighter valuable products are formed.

10.RANEYNICKEL catalyst used to reduce organic sulfur compounds.

9.FERROCENE a redox catalyst in organic synthesis

4.ALUMINUMCHLORIDE type of Lewis acid catalyst used in acylations

6.PALLADIUM electrocatalyst for oxidation of primary alcohols in alkaline media

3.RADICAL free agent in chemistry 🙂

2.EPOXIATION transfer of an oxygen atom from a peroxy compound to an alkene.

8.SELECTIVITY degree of a reaction to yield a specific product.