Dear Catalysis Researchers,

Welcome to the Magic Powder Newsletter!

We are excited to present the 11th edition of the Magic Powder newsletter, bringing you one step closer to the fascinating world of catalysts! This month, we’re thrilled to share the latest developments in catalysis research and inspiring stories from scientists.

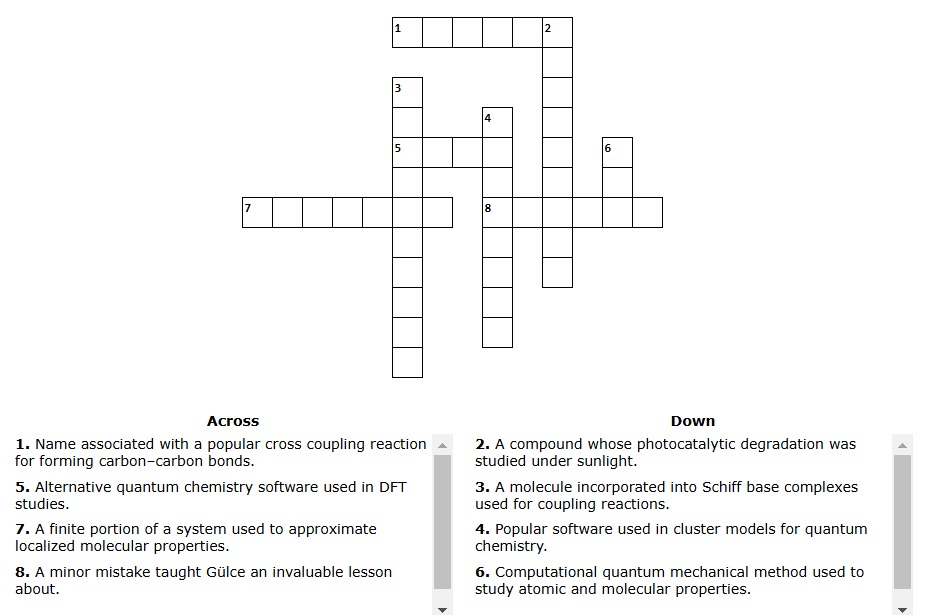

In this issue, you will explore how computational methods, such as Density Functional Theory (DFT), have revolutionized catalysis research with insights from Dr. M. Oluş Özbek from Gebze Technical University. Additionally, Dr. Gülce Çakman shares her PhD journey, illustrating how unexpected and fun this path can be. From small accidents in the lab to late-night experiments and the thrill of scientific discoveries, all of these remind us that science is not only a serious discipline but also an exciting adventure. We’ve also included summaries of recently published academic papers in the field of catalysis. In this issue we did not forget to challenge you with our puzzle from Professor Merlin Catalystorius

As a catalysis community, we also share with you a vibrant program of events scheduled for 2025. Join us on this journey from Sivas to Romania, from Norway to Bolu, to stay updated on the latest developments in the world of catalysis.

Enjoy your reading! 🚀🔬

The Catalysis Society

Editorial Board

Prof. Dr. Ayşe Nilgün AKIN

Prof. Dr. N. Alper TAPAN

Dr. Merve DOĞAN ÖZCAN Asst. Prof. Dr. Elif CAN ÖZCAN

Dr. Mustafa Yasin ASLAN

Applications for Density Functional Theory in Catalysis Research

By Assoc. Prof. Dr. M. Oluş Özbek

With rapid advancements in computer technologies and computational algorithms, the accuracy of computational methods has significantly improved, enabling researchers to gain unprecedented insight into complex chemical processes. This progress has not only deepened our understanding of fundamental reaction mechanisms but has also revolutionized catalysis research, providing powerful tools to design and optimize catalysts for industrial applications. To comprehend how Density Functional Theory (DFT) can be applied to catalysis research, it is essential to first delve into the history and development of DFT. Understanding its origins and fundamental principles provides a clearer picture of what DFT can achieve and the unique insights it offers into chemical processes.

DFT is a computational quantum mechanical method used to study the properties of atoms, molecules, and solids. In its most basic form, it solves the ground state electronic configuration of the given system. The starting point of DFT is the many-body Schrödinger’s Equation (ĤΨ = EΨ), formulated in 1926, and was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1933. Although this equation is exact, its solution is computationally impractical for large systems. The first practical approximate solution was introduced by Hartree in 1928 [1], who decomposed the total wave function as a product of single-electron wave functions (Ψ ≈ Π ψi). This approach enabled the transformation of the many-body (i.e., many-electron) Schrödinger equation into a set of one-electron equations. However, this significant simplification neglected the electron exchange and correlation effects. This approximation has limited accuracy because i. the physical state of a system must be invariant under the exchange of electrons (i.e., electrons are not distinguishable) and ii. the correlation arises from the fact that electrons interact via Coulomb forces, which are instantaneous and depend on their relative positions.

To address the shortcomings of the Hartree method, Fock and others introduced the Hartree-Fock (HF) method (1930) [2], which incorporated the Pauli exclusion principle. The HF method improved upon Hartree’s approximation by using a combination of single-electron wave functions (the Slater determinant) to construct the many-electron wave function. Although the HF method introduces an approximate exchange interaction through mean field approximation and can be solved iteratively (i.e., a self-consistent solution can be reached), it still neglects electron correlation. Another problem with the HF method is being computationally expensive due to high degrees of freedom (DOF). At this point, the DFT method used the electron density ρ(r), which depends only on three spatial variables, reducing the DOF and making a huge gain in the computation load.

One of the earliest density-based methods was the Thomas-Fermi model (1927–1928) [3,4], which approximated the energy of a system as a functional of the electron density. In 1964, Hohenberg and Kohn established the modern formalism of DFT by incorporating two theorems with their infamous ‘Inhomogeneous Electron Gas’ [5]: i. The ground-state properties of a many-electron system are uniquely determined by its electron density ρ(r), and ii. The energy of the system can be expressed as a functional E[ρ], which is minimized at the true ground-state density. Today the main form of DFT is based on the Kohn-Sham (KS) equations, developed by Kohn and Sham in 1965 [6], and was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1998. Their method introduced virtual orbitals (KS orbitals) that enabled the decomposition of energy functional E[ρ] into components such as kinetic energy, classical electrostatic energy, and exchange-correlation energy.

The success of DFT depends on two basic components. The first is the basis set used to describe the electronic structure of the atoms. A better representation would need a larger basis set that includes a larger number of parameters. However, since each new variable increases the DOF from 2n to 2n+1 (approx.), the selection of a suitable basis set is a trade-off between computational load and model correctness. Apart from the all-electron applications, most of the basis sets lighten the computational load using core (fixed) and valence (variable) electrons.

Among these, pseudopotentials are commonly used and have a semi-empirical nature. The second component is the exchange correlation function that describes (or solves for) the interactions between the electrons of these atoms. It would not be totally wrong to say that the improvement in DFT applications stems from the improvements in the exchange functionals. After the first Local Density Approximation (LDA) [6] was introduced in 1965, the improvement came with Generalized Gradient Approximation (GGA) [7] in 1992. The GGA functional was further improved to overcome the shortcomings through PBE [8] in 1996 and RPBE [9] in 1999. To overcome the shortcomings of the pure GGA, hybrid functionals that include the HF into the exchange were developed, such as B3LYP [10] and PBE0 [11]. These hybrid functionals significantly improved the accuracy of the results; however, at a higher computational cost, rendering them impractical for larger systems. This chronological progression of exchange-correlation functionals highlights the continuous efforts to balance accuracy, computational efficiency, and versatility, enabling DFT to become a cornerstone of quantum chemistry and materials science.

Currently Wikipedia lists more than 50 commonly used software [12]. These can be grouped into two categories with respect to their applications. First is the cluster models (Figure 1), which uses software such as Gaussian and ORCA and involves the approximation of a finite portion of a system, such as a molecule or a localized region of a material, to simulate its properties. These models are particularly useful for studying small-scale systems (isolated molecules) or specific reaction sites [13], allowing detailed study of localized interactions at a lower computational cost. While surface reactions can be modeled using a large enough cluster [14], this method suffers from edge effects and is not able to represent bulk properties.

Second group is the periodic models that use software like VASP or Quantum Espresso and utilize planewave basis sets, which are periodic themselves. As the name implies, these models use periodic boundary conditions to simulate infinite systems by repeating a unit cell. This approach is widely employed for studying crystalline solids, surfaces, and materials with translational symmetry. The major advantage over the cluster models is the ability to accurately represent materials with periodic structures, capturing long-range interactions and electronic band structures. These are especially well-suited for interpreting spectroscopic or crystallographic measurements. Practical applications cover simulations of surfaces and surface reactions, thin films, and interfaces under realistic conditions. Once again, the trade-off for these realistic models is the higher computational cost and complexity of setup. Not widely applied, but a combination of both approaches for comprehensive insights is also possible [15].

Figure 1: A non-periodic copper cluster placed on a periodic ZnO surface [16].

Working at the electronic level, DFT is a powerful tool for interpreting and forecasting experimental data through simulations. As the theory dictates, the basic output of DFT is the ground-state geometry and the corresponding electronic structure and energy. When bulk materials are considered, even this basic output can be used to identify the band structure and the density of state (DOS) [17]. Similarly, surface and interface properties, such as surface energies or surface reconstructions, can be predicted and studied [18]. When a reacting system is considered, the basic output contains necessary information to determine thermodynamic properties such as reaction enthalpies or relative stability. Going one more step from the ground state, molecular vibrations can be computed. By using vibrational data through partition functions, the enthalpy values initially obtained at zero temperature and pressure can be converted to free energies that are physically more meaningful. Furthermore, inclusion of the transition state theory enables the computation of the transition states along the reaction coordinate. In this manner, DFT identifies reaction pathways, locates transition states, and calculates reaction and activation energies [19]. Using this data in combination with statistical thermodynamics also enables determination of the reaction rate constants.

Figure 2: Experimental and simulated STM images for the MoS2 monolayers [22].

When the aim is to deepen the understanding of catalytic systems, it can be utilized in two main ways. The first way is a feedback route that investigates the existing experimental data at the molecular level. In this way, DFT uses electronic level resolution to understand the catalytic systems at a molecular level. As already mentioned above, when experimental analysis is not possible, available, or feasible, DFT models can identify the unobserved phenomena. At this point, however, a good and validated foundation is required. Comparison with the existing experimental data or measurements is a good starting point. Depending on the available measurements, the DFT model can be validated using basic outputs. If the experimental analysis is available on physical structure, such as SEM, TEM, AFM, STM, or LEED, then model geometry (and corresponding electronic density) can be used (Figure 2). Further structural analysis is also available by NMR simulations [17] as well. The analysis based on electronic excitations such as XPS or UV-Vis can also be simulated by using time-dependent DFT (TD-DFT) [20].

When the focus shifts from structural analysis to kinetic analysis, DFT simulations can be used to identify the selective and unselective reaction routes, stepwise and apparent activation barriers, and kinetic constants that would (or should) match the kinetic, calorimetric, and adsorption experiments (Figure 3). Furthermore, in the case of surface science type studies, surface-adsorbate interactions, stable surface species, coverage, and co-adsorption effects can be identified through simulations. Similarly, computation of the molecular vibrations would produce the results for experimental IR and RAMAN analysis [21]. In the second (feed-forward) approach, DFT simulations can be used to lighten the load of the experimental work. Prior to experimental work, many possibilities or candidates can be tested rapidly and economically to identify the desired outcomes and eliminate the undesired ones.

Figure 3: Potential energy diagram for the surface carbon hydrogenation, regeneration, and water formation on the Hagg-carbide surface [19].

As can be seen, DFT models can be used to predict or reproduce almost all the experimental analysis used for catalysis research. Once the existing analysis is used to verify the DFT model, more detailed analysis that are not possible or feasible experimentally can be carried out through DFT simulations for a molecular-level insight into the system. However, it should not be forgotten that DFT’s results depend on the application and the model. That is the output only shows the effects and interactions of simulation box contents. Thus, models should be prepared with the identification and foresight of the principal factors and components that would affect the outcome. That’s why experiments and DFT simulations share a mutual relationship, where each enhances the other’s impact. Experiments provide crucial guidance for constructing realistic models in DFT simulations, ensuring that theoretical studies are grounded in practical observations. In turn, these realistic models enable DFT simulations to offer detailed molecular-level insights, helping to explain and interpret experimental results. This synergy not only bridges the gap between theory and practice but also advances our understanding of complex chemical and physical phenomena.

Density Functional Theory had a strong impact on catalysis research, offering valuable insights into reaction mechanisms, energy landscapes, and catalyst design. As computational power continues to grow and new algorithms emerge, the future lies in integrating DFT with advanced techniques like machine learning and multi-scale simulations to push the boundaries of what is computationally possible.

References

[1] D.R. Hartree, The Wave Mechanics of an Atom with a Non-Coulomb Central Field. Part I. Theory and Methods, Mathematical Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society 24 (1928) 89–110. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305004100011919.

[2] V. Fock, Näherungsmethode zur Lösung des quantenmechanischen Mehrkörperproblems, Zeitschrift Für Physik 61 (1930) 126–148. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01340294/METRICS.

[3] L.H. Thomas, The calculation of atomic fields, Mathematical Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society 23 (1927) 542–548. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305004100011683.

[4] E. Fermi, Eine statistische Methode zur Bestimmung einiger Eigenschaften des Atoms und ihre Anwendung auf die Theorie des periodischen Systems der Elemente, Zeitschrift Für Physik 48 (1928) 73–79. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01351576/METRICS.

[5] P. Hohenberg, W. Kohn, Inhomogeneous electron gas, Physical Review 136 (1964). https://doi.org/10.1103/PHYSREV.136.B864/FIGURE/1/THUMB.

[6] W. Kohn, L.J. Sham, Self-consistent equations including exchange and correlation effects, Physical Review 140 (1965). https://doi.org/10.1103/PHYSREV.140.A1133/FIGURE/1/THUMB.

[7] J.P. Perdew, Y. Wang, Accurate and simple analytic representation of the electron-gas correlation energy, Phys Rev B 45 (1992) 13244. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.45.13244.

[8] J.P. Perdew, K. Burke, M. Ernzerhof, Generalized Gradient Approximation Made Simple, Phys Rev Lett 77 (1996) 3865. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.3865.

[9] B. Hammer, L.B. Hansen, J.K. Nørskov, Improved adsorption energetics within density-functional theory using revised Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof functionals, Phys Rev B 59 (1999) 7413. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.59.7413.

[10] C. Lee, W. Yang, R.G. Parr, Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density, Phys Rev B 37 (1988) 785–789. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.37.785.

[11] C. Adamo, V. Barone, Toward reliable density functional methods without adjustable parameters: The PBE0 model, J Chem Phys 110 (1999) 6158–6170. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.478522.

[12] wikipedia, List of quantum chemistry and solid-state physics software, Https://En.Wikipedia.Org/Wiki/List_of_quantum_chemistry_and_solid-State_physics_software (n.d.).

[13] M.F. Fellah, R.A. Van Santen, I. Onal, Oxidation of benzene to phenol by N2O on an Fe 2+-ZSM-5 cluster: A density functional theory study, Journal of Physical Chemistry C 113 (2009) 15307–15313. https://doi.org/10.1021/JP904224H/ASSET/IMAGES/LARGE/JP-2009-04224H_0001.JPEG.

[14] M.F. Fellah, R.A. Van Santen, I. Onal, Epoxidation of ethylene by silver oxide (Ag2O) cluster: A density functional theory study, Catal Letters 141 (2011) 762–771. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10562-011-0614-2/METRICS.

[15] C. Ricca, F. Labat, C. Zavala, N. Russo, C. Adamo, G. Merino, E. Sicilia, B,N‐Codoped graphene as a catalyst for the oxygen reduction reaction: Insights from periodic and cluster DFT calculations, J Comput Chem 39 (2018) 637–647. https://doi.org/10.1002/JCC.25148.

[16] Q.L. Tang, W.T. Zou, R.K. Huang, Q. Wang, X.X. Duan, Effect of the components’ interface on the synthesis of methanol over Cu/ZnO from CO2/H2: a microkinetic analysis based on DFT + U calculations, Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 17 (2015) 7317–7333. https://doi.org/10.1039/C4CP05518G.

[17] E. Mete, S. Odabaşl, H. Mao, T. Chung, Ş. Ellialtloǧlu, J.A. Reimer, O. Gülseren, D. Uner, Double Perovskite Structure Induced by Co Addition to PbTiO₃: Insights from DFT and Experimental Solid-State NMR Spectroscopy, Journal of Physical Chemistry C 123 (2019) 27132–27139. https://doi.org/10.1021/ACS.JPCC.9B06396/ASSET/IMAGES/LARGE.

[18] A.T. Ta, R.S. Ullberg, S.R. Phillpot, Surface reconstruction and cleavage of phyllosilicate clay edge by density functional theory, Appl Clay Sci 246 (2023) 107178. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CLAY.2023.107178.

[19] M.O. Ozbek, J.W. Niemantsverdriet, Methane, formaldehyde, and methanol formation pathways from carbon monoxide and hydrogen on the (0 0 1) surface of the iron carbide χ-Fe5C2, J Catal 325 (2015) 9–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JCAT.2015.01.018.

[20] I. Gokce, M.O. Ozbek, B. Ipek, Conditions for higher methanol selectivity for partial CH4 oxidation over Fe-MOR using N2O as the oxidant and comparison to Fe-SSZ-13, Fe-SSZ-39, Fe-FER, and Fe-ZSM-5, J Catal 427 (2023) 115113. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JCAT.2023.115113.

[21] B. Caglar, M. Olus Ozbek, J.W. Niemantsverdriet, C.J. Weststrate, The effect of C–OH functionality on the surface chemistry of biomass-derived molecules: ethanol chemistry on Rh(100), Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 18 (2016) 30117–30127. https://doi.org/10.1039/C6CP06069B.

[22] J. Hong, Z. Hu, M. Probert, K. Li, D. Lv, X. Yang, L. Gu, N. Mao, Q. Feng, L. Xie, J. Zhang, D. Wu, Z. Zhang, C. Jin, W. Ji, X. Zhang, J. Yuan, Z. Zhang, Exploring atomic defects in molybdenum disulphide monolayers, Nature Communications 2015 6:1 6 (2015) 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms7293.

PhD Stories

Hello, I am Gülce ÇAKMAN. I earned my PhD in 2023 from Department of Chemical Engineering at Gazi University. Concurrently, I have been working as a Research Assistant in the Department of Chemical Engineering at Ondokuz Mayıs University. My doctoral research focused on catalyst synthesis and reaction activity. Describing my PhD journey (6.5 years ) feels a lot like explaining a laboratory experiment: a process that seems under control at first but gradually evolves under the influence of numerous variables.

During my PhD, travelling between Ankara and Samsun became a regular part of my life—a true academic marathon. Sometimes I was sleep-deprived, sometimes exhausted, but it was always an interesting and entertaining experience. During the coursework phase, I traveled to Ankara every week for classes. One day when I had a morning class, I didn't have time to go home, so I went straight to the lab. Thinking I could take a quick nap, I set an alarm and dozed off on a chair. Unfortunately, although the alarm did ring, it took me longer than expected to wake up. Despite being at the university bright and early, I ended up missing my first lecture. This was one of the first times I learned how academic life can be full of such ironies.

Laboratory days were even more exciting. Planning experiments felt exciting, and I initially believed I could achieve my desired results quickly. However, once I stepped into the laboratory, I realized that things were far more complex. Every day brought unexpected challenges, teaching me the importance of patience throughout the PhD journey. Towards the end of my doctoral work, I learned firsthand how power fluctuations could chaos during experiments. Everything was going smoothly until the computer screen began flickering and then completely shut down. Simultaneously, a small plume of smoke emerged from a nearby device. I immediately unplugged the equipment, but while trying to figure out what had gone wrong, I noticed a small fire had broken out. My colleague and I quickly extinguished it using the first lab coat we could grab. This minor mishap not only added excitement to the day but also taught me an invaluable lesson about lab safety. Ever since that incident, the first thing I do in any lab is locate the circuit breakers and fire extinguishers.

The challenges I encountered during my PhD, coupled with these humorous anecdotes, made the experience truly unforgettable. Now, as a Research Assistant with a PhD, I enjoy sharing these stories as they reflect both the discipline required for scientific research and the unexpected situations that arise during the process. I’ve learned that scientific journeys rarely go as planned, but every step is profoundly educational. Currently, I am at a new stage of my academic career. I continue my work as a Research Assistant with a PhD and I am awaiting a position as an Assistant Professor. In the meantime, my projects and research activities are ongoing. While I eagerly anticipate the next step, I continue to embrace the unique rhythm and humor of academic life.

Recent Selected Papers in Our Catalysis Community

In recent months, there have been exciting research studies in catalysis research in Turkey.

Here are the short summaries:

Methane Reforming

Pehlivan, T., Özdemir, H., Gürkaynak Altınçekiç, T., Öksüzömer, M.A. Faruk. (2024). Oxy-CO2 reforming of methane on Al2O3, MgAl2O4, CeO2 and ZrO2 supported Ni catalysts prepared by deposition-precipitation method. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 96, 703–710.

Nickel catalysts (15 wt%) supported on Al₂O₃, MgAl₂O₄, CeO₂, and ZrO₂ were synthesized using the deposition-precipitation method and evaluated for their performance in oxy-CO₂ reforming of methane. The results indicate that specific surface area, support type, and surface properties play critical roles in determining catalytic activity, with higher Ni concentration and larger surface area contributing to improved performance. Among the tested catalysts, the 15 wt% Ni/Al₂O₃ catalyst synthesized via the urea deposition-precipitation method demonstrated the most promising activity.

Kesan Celik, N., Yasyerli, S., Arbag, H., Tasdemir, H.M., Yasyerli, N. (2025). Regenerable nickel catalysts strengthened against H2S poisoning in dry reforming of methane. Fuel, 383, 133903.

Alumina-supported Ni-Cu and Ni-Cu-Ce catalysts were synthesized to improve resistance to coke formation and sulfur poisoning in the dry reforming of methane (DRM). The 8Ni-3Cu-8Ce catalyst, prepared via the impregnation method, exhibited superior stability and activity compared to the Ni-Cu catalyst, particularly in H₂S-containing environments, with cerium and copper enhancing sulfur tolerance. Regeneration studies demonstrated that the catalyst could be effectively restored using a low oxygen concentration, underscoring its potential for industrial applications.

Organic Synthesis, Computational Chemistry

Inan Duyar, A., Sünbül, A.B., Serin, S., Dogan Ulu, Ö., Ozdemir, İ., Ikiz, M., Köse, M., Ispir, E. (2025). Synthesis, characterization, DFT quantum chemical calculations and catalytic properties of azobenzene-bearing Schiff base palladium (II) complexes for the Suzuki-Miyaura Cross-Coupling reaction in aqueous solvent. Journal of Molecular Structure, 1328, 141296.

A series of azobenzene-bearing Schiff base ligands and their homoleptic Pd(II) complexes were synthesized and characterized using NMR, FTIR, UV-Vis spectroscopy, and elemental analysis. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed to optimize the structures of the

Pd(II) complexes, revealing high reactivity with ΔE values ranging from 3.136 to 3.239 eV. These complexes demonstrated excellent catalytic activity in Suzuki–Miyaura coupling reactions, with catalysts 12 and 15 achieving the highest yields in the presence of electron-withdrawing groups.

CO2 Utilization

Aytar, E., Kibar, M.E. (2025). An assessment of boron-doped nanotube TiO2 as effective catalysts for CO2 fixation with epoxide to form cyclic carbonates. Inorganic Chemistry Communications, 173, 113909.

The conversion of CO₂ into cyclic carbonates is a crucial approach to CO2 fixation, advancing green chemistry and carbon neutrality. In this study, boron-doped nanotube TiO2 catalysts (B1-ntTiO2 and B16-ntTiO2) were synthesized and evaluated for CO2 insertion into epoxides, with B16-ntTiO2 achieving 96% efficiency and 99.2% selectivity under optimal conditions. Although its efficiency decreased to 80% after three cycles, it retained approximately 99% selectivity, demonstrating its potential as a sustainable alternative to toxic reagents such as phosgene.

Conductive Materials

Öztekin, D., Arbağ, H., Yaşyerli, S. (2024). Preparation of RGO with Enhanced Electrical Conductivity: Effects of Sequential Reductions of L-Ascorbic Acid and Thermal. Arabian Journal for Science and Engineering, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13369-024-09915-5

This study optimized the reduction of graphene oxide (GO) using L-ascorbic acid and H₂ at moderate temperatures to synthesize reduced graphene oxide (RGO) with high electrical conductivity. The RGO-AA-T material, which underwent sequential chemical and thermal reduction, exhibited the highest conductivity (1.97 × 10⁴ S/m) and a C/O ratio of 15.5, attributed to the formation of fewer graphene layers and denser sp² domains. These findings demonstrate that the chemical-thermal reduction sequence effectively removes oxygen functional groups, restores sp² domains, and significantly enhances electrical conductivity, establishing it as a promising method.

Photocatalysis

Bouziani, M., Bouziani, A., Hsini, A., Bianchi, C.L., Falletta, E., Michele, A.D., Çelik, G., Hausler, R. (2025). Synergistic photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue and ibuprofen using Co₃O₄-Decorated hexagonal boron nitride (hBN) composites under Sun-like irradiation. Chemosphere, 371, 144061.

This study investigates the synthesis and photocatalytic performance of Co₃O₄-decorated hexagonal boron nitride (hBN) composites for the degradation of methylene blue and ibuprofen under sunlight irradiation. The 1% Co₃O₄-hBN composite exhibited the highest activity, achieving nearly complete methylene blue degradation within 60 minutes and 90% ibuprofen degradation within 120 minutes, attributed to enhanced light absorption and charge separation. These findings underscore the potential of Co₃O₄-hBN composites for environmental remediation and highlight the need for further research on their stability and broader applications.

Electrocatalysis

Yıldırım, N., Tapan, N.A. (2025). Synthesis and characterization of graphene-based electrocatalysts for the detection of damaged starch ratio Fullerenes, Nanotubes and Carbon Nanostructures, https://doi.org/10.1080/1536383X.2024.2449066.

This study assessed graphene-based electrocatalysts for the detection of damaged starch ratios through the iodine oxidation mechanism. Electrocatalysts synthesized via three electrochemical exfoliation techniques were evaluated in a three-electrode system using cyclic voltammetry and chronoamperometry. Among the tested electrocatalysts, G2 exhibited the highest sensitivity to iodine absorption, demonstrating its potential for damaged starch detection.

Previous issue answers Newsletter #10:

1. Boudouard, 2. HZSM, 3. Popper, 4. Microwave, 5. Esterification, 6. EuropaCat, 7.CREG, 8. Carbide

Announcements

In 2025, there will be a highly active program of events in the field of catalysis.

• From June 25 to 28, 10th National Catalysis Conference (NCC10), organized by the Catalysis Society and Cumhuriyet University, will take place in Sivas. We look forward to welcoming you there.

• From July 9 to 11, The 14th International Symposium of the Romanian Catalysis Society (RomCat 2025), organized by Societatea De Cataliza Din Romania will be held on Gluj-Napoca, Romania. For more information: http://www.unibuc.ro/romcat/

• From August 31 to September 5, 16th Europacat Conference, organized by EFCATS, of which our society is a member, will be held in Trondheim, Norway.

• From September 1 to 4, 36th National Chemistry Congress, organized by Van Yüzüncü Yıl University will feature a "Catalysis" session supported by Catalysis society."

• From September 9 to 12, the 16th National Chemical Engineering Congress, organized by Bolu Abant İzzet Baysal University, will host a special session on "Catalysis and Reaction Engineering," supported by Catalysis society.

• The annoucment on MaCKiE Conference is given below:

Dear Members,

The MaCKiE Conference, officially known as the International Conference on Mathematics in (bio)Chemical Kinetics and Engineering, is an international chemical engineering conference that has been held ten times before and will take place in Türkiye this year. The conference aims to explore the fundamentals of the discipline and the design, development, and improved understanding of new chemical and biochemical engineering processes through mathematical modeling.

Initiated by Guy B. Marin, Gregory Yablonsky, and Denis Constales from Ghent University in Belgium, this year's conference will be held on September 4-6 at the Radisson Blu Hotel in Çeşme. A significant part of the conference will focus on designing new and sustainable processes in chemical engineering. The event will feature invited speakers not only from Europe but also from the United States, China, and the Middle East.

You can find details about the invited speakers and all other information on the conference website: https://mackieturkey.com/

We wish everyone a successful and fulfilling year in catalysis and look forward to seeing you at these events!