Dear Catalysis Enthusiasts,

Welcome to the 14th issue of Magic Powder, your gateway to the dynamic and ever-evolving world of catalysis. As we navigate the complexities of chemical transformations, this issue brings you timely insights and practical guidance on some of the most critical aspects of our field. We open with an in-depth exploration of accurate kinetic measurements in flow systems by Prof. Dr. Alper Uzun—an essential read for anyone aiming to bridge experimental rigor with real-world catalytic performance. We also feature a comprehensive overview of CO₂ hydrogenation by Dr. Merve Doğan Özcan, shedding light on its potential to revolutionize sustainable fuel and chemical production.

In addition to our technical features, this edition celebrates the human side of scientific pursuit. Dr. Nurbanu Çakıryılmaz Şahingöz shares her compelling PhD journey, offering an honest and inspiring look at balancing academic ambition with professional and personal life. You’ll also find highlights from recent publications within our catalysis community, showcasing innovative research across areas such as gas separation, biodiesel production, photocatalysis, and machine learning applications.

For those looking to engage their minds in a more playful way, we invite you to try our Crossword Puzzle—a fun challenge inspired by catalytic concepts—and take a moment to reflect with selections from the Catalytic Wisdom Guide, where Professor Merlin Catalystorius blends wit and wisdom to remind us why we fell in love with catalysis in the first place.

Finally, don’t forget to mark your calendars for the upcoming 10th National Catalysis Conference (NCC10), taking place in Sivas from June 25–28, 2025. With a vibrant scientific program and opportunities to connect with fellow researchers, it promises to be one of the highlights of the year for our community.

We hope this issue sparks new ideas, fuels your curiosity, and reminds you that behind every catalyst is a passionate scientist pushing boundaries.

The Catalysis Society

Editorial Board

Prof. Dr. Ayşe Nilgün AKIN

Prof. Dr. N. Alper TAPAN

Dr. Merve DOĞAN ÖZCAN

Asst. Prof. Dr. Elif CAN ÖZCAN

Dr. Mustafa Yasin ASLAN

Measuring What Matters: Accurate Catalytic Testing in Flow Systems

By Prof. Dr. Alper Uzun

Koç University

Chemical and Biological Engineering Department

Abstract

Reliable measurement of catalytic performance is fundamental to understanding reaction mechanisms, assessing intrinsic activity, and developing structure–activity relationships. This note provides a comprehensive guide to best practices for conducting kinetic studies using flow reactor systems. Emphasis is placed on maintaining reaction-controlled conditions by minimizing heat and mass transfer limitations, ensuring isothermal operation, and conducting experiments under differential conversions. Practical strategies, including catalyst dilution, pressure monitoring, and careful reactor configuration, are discussed in detail. Key concepts such as thermodynamic constraints, turnover frequency (TOF), and the importance of accurately characterizing active sites are addressed to promote meaningful data interpretation and catalyst comparison. Designed as a hands-on resource, this guide is particularly suited for early-career researchers aiming to establish rigorous and reproducible catalytic testing protocols in flow systems.

Main

Catalysis may seem simple at first. You synthesize a catalyst—much like preparing a recipe in your kitchen—load it into a reactor, introduce the reactants, and analyze the products to determine conversion rates and product selectivities. But the real complexity emerges when you begin to ask deeper questions: What are the true active sites responsible for driving the desired reactions? The challenge grows as you attempt to unravel the intricate relationships between catalyst structure and performance. And it turns into a true passion when you realize that the textbook definition of a catalyst—a substance that speeds up a reaction without undergoing any change—is, in practice, an oversimplification. In reality, catalysts evolve, restructure, and interact dynamically with their environment, and understanding these transformations is at the heart of advancing catalytic science.

Crucially, the path forward in catalysis lies in ensuring that performance measurements truly reflect intrinsic reaction kinetics. This requires complete control over experimental conditions—decoupling surface chemistry from mass and heat transport limitations. Mastering this balance elevates catalysis from a science to an art.

In this note, I aim to share the hands-on insights I’ve gained over the past 25 years, working closely with some of the leading scientists in the field. My focus will be on operations using flow reactor systems—where rigor in experimental design and execution is essential to uncover meaningful structure–activity relationships and reliable kinetic data.

Figure 1 shows the schematic overlay of one of the high-pressure flow reactor systems used in the Uzun Lab at Koç University. This system is designed for the evaluation of solid catalysts under two-phase or three-phase conditions and is capable of operating at pressures up to 100 bar and 1100 C. It is equipped with multiple mass flow controllers and two high-pressure syringe pumps, which feed reactants into the system. A downstream back-pressure regulator maintains the desired operating pressure, enabling precise control during high-pressure experiments.

Figure 1. Diagram of a high-pressure three-phase flow reactor system used for glycerol etherification with isobutene.1

A key feature of the system is its three-zone furnace, which allows independent temperature control across different sections of the reactor. This design enables us to preheat the feed before it contacts the catalyst bed, ensuring that reactions occur at the intended temperature. Additionally, pressure gauges installed before and after the reactor allow real-time monitoring of system pressure and provide a means to detect pressure drops across the catalyst bed.

Monitoring pressure drop is critical, especially in three-phase systems. For instance, during high-pressure glycerol etherification, a reaction used to produce fuel additives, the viscosity of glycerol and the use of finely powdered catalysts can cause substantial pressure drops. This becomes problematic for several reasons: First, one fundamental assumption in catalytic testing is that all catalyst particles experience the same reactant composition. However, significant pressure drops can create gradients in concentration, particularly if one or more reactants are in the gas phase, thereby invalidating this assumption and biasing activity measurements. Second, the flow might completely stop if the supply pressure of the feed can not overcome the pressure drop, in this case the measurement completely fails as the desired space velocity can not be maintained. Third, and more importantly, large pressure drops present serious safety concerns. Excessive pressure can exceed the mechanical limits of fittings, potentially causing leaks or failures, especially hazardous when working with toxic, flammable, or explosive chemicals.

To mitigate such risks, it is standard practice to install a pressure relief valve upstream of the reactor. This provides a fail-safe mechanism: if the pressure rises excessively due to blockage or a severe pressure drop across the catalyst bed, the system can vent the excess pressure safely. This precaution is vital for maintaining both data integrity and operational safety.

Maintaining isothermal conditions within the reactor is another crucial aspect for obtaining reliable kinetic data. This becomes particularly challenging for highly exothermic reactions, especially when the desired operating temperature is only slightly above ambient conditions. Without proper thermal management, localized temperature spikes, commonly referred to as hot spots, can lead to non-uniform reaction conditions, catalyst deactivation, or misleading activity data.

A common and effective strategy to mitigate this issue is to dilute the catalyst with an inert material, such as silica, silicon carbide, or alundum. These materials help dissipate heat and reduce the risk of hot spots within the catalyst bed. The optimal catalyst-to-inert dilution ratio depends on several key factors, including allowable pressure drop, reactor volume, and the desired space velocity range for testing. As a general rule of thumb, a starting ratio of at least 1:100 (catalyst to inert, by weight or volume) often provides a good baseline for further optimization under specific reaction conditions.

It is also important to ensure consistency in the mesh sizes of the catalyst and inert materials. A mismatch—particularly if the catalyst particles are significantly finer—can lead to particle segregation over time. This issue is especially pronounced during prolonged operation under high pressure, where finer particles tend to migrate and accumulate at the bottom of the catalyst bed, potentially distorting temperature, flow, and reaction profiles.

Another effective strategy for promoting isothermal operation is to fill the dead volume above the catalyst bed with an inert material. This section acts as a thermal buffer, allowing the feed to preheat before contacting the catalyst. By the time the reactants reach the catalyst bed, they are closer to the desired reaction temperature, minimizing axial temperature gradients and ensuring more uniform reaction conditions. To limit additional pressure drop, the inert packing material used in this preheating zone can be relatively coarse in particle size. This maintains low flow resistance while still providing sufficient thermal mass to preheat the feed effectively.

In addition to engineering strategies, the Anderson criterion is a key quantitative tool for evaluating whether a reactor operates under isothermal conditions. It compares the heat generation rate from the reaction with the system's heat removal capacity (via conduction, convection, or cooling mechanisms). This ensures that reaction rates reflect intrinsic kinetics and are not distorted by temperature gradients. For highly exothermic reactions, it is essential for validating kinetic measurements and confirming accurate reactor operation.2

Once stable operation under the desired conditions is confirmed, meaning that temperature, pressure, and space velocity are properly established and consistently maintained, kinetic data collection can begin. However, before initiating any experimental campaign, it is imperative to assess the thermodynamic limits of the reaction. Thermodynamics governs all physical and chemical transformations, and catalytic processes are no exception. Specifically, the maximum achievable conversion in a catalytic reactor is constrained by the chemical equilibrium of the system. No matter how active or selective the catalyst may be, it cannot overcome the limits set by equilibrium. Therefore, prior to conducting any kinetic measurements, one must first calculate the equilibrium constant (Keq) for the reaction of interest under the intended reaction conditions (temperature and pressure). This allows the determination of the equilibrium conversion (Xeq), which serves as a theoretical upper bound under given condition.

Figure 2. a) Variation of equilibrium methanol yield with feed composition,3 b) tandem reaction pathway by the presence of acidic function to consume methanol as soon as it formed to overcome the equilibrium limitations.4

As an illustrative example, Figure 2 shows the equilibrium conversion for methanol synthesis from synthesis gas—a reaction of significant industrial relevance. Under typical conditions of 30 bar and 250 °C, and in the absence of CO in the feed, the equilibrium methanol yield is limited to approximately 10% (with respect to CO2). This value represents a strict thermodynamic ceiling: no matter how active the catalyst, conversion cannot exceed this limit under those conditions. However, this constraint can be circumvented by introducing a secondary catalytic function that consumes the product as soon as it forms, converting it into another compound. For instance, in methanol synthesis, incorporating an acidic functionality enables the downstream conversion of methanol into dimethyl ether (DME) and tremendously improves the CO2 conversion. This tandem reaction pathway shifts the equilibrium, allowing higher overall conversion of the feedstock, at the expense of reduced selectivity toward methanol. Critically, reporting catalyst performance at or near equilibrium conversion offers little to no insight into the true kinetic behavior of the system. At equilibrium, the forward and reverse reaction rates are equal, and any net conversion is dictated purely by thermodynamics, not by catalyst properties. Therefore, to extract meaningful kinetic parameters, the reactor must be operated well below the equilibrium conversion, where the system is under kinetic control rather than thermodynamic constraint. This underscores the importance of choosing appropriate space velocities: they must be high enough to avoid equilibrium limitations, yet low enough to maintain measurable conversion and avoid mass transfer artifacts. Careful balance and pre-assessment of equilibrium constraints are thus essential or the rational design of catalytic experiments and for ensuring the relevance of the resulting data.

Accurate measurement of reaction kinetics requires that the system operates under reaction-controlled conditions, where the intrinsic surface reaction is the rate-limiting step. This is a fundamental principle in reaction engineering and is critical for extracting meaningful kinetic parameters.

Figure 3 illustrates the series of elementary steps involved in a catalytic reaction occurring at active sites located deep within the pores of a solid catalyst particle. The overall process involves both transport phenomena and surface chemistry. It can be broken down into the following sequence:

Step 1. External mass transfer: Reactant molecules must first traverse a boundary layer (often idealized as a thin film) surrounding the catalyst particle.

Step 2. Pore diffusion: Upon reaching the external surface, reactants diffuse through the porous network of the catalyst. Depending on the pore size and operating conditions, this step may be governed by molecular diffusion, Knudsen diffusion, or a combination of both.

Step 3. Adsorption: The reactant molecules adsorb onto the catalyst's active sites.

Step 4. Surface reaction: The adsorbed species undergo chemical transformation to form the desired product.

Step 5. Desorption: The product molecules desorb from the active site.

Step 6. Intra-particle diffusion (back): The product diffuses out of the pores.

Step 7. External mass transfer (back): Finally, the product crosses the external film and enters the bulk fluid.

Figure 3. The seven steps of a catalytic reaction.5

Of these seven steps, the reaction rate is the quantity of interest in kinetic studies. Therefore, to ensure the measured rate truly reflects the intrinsic kinetics, the surface reaction must be the slowest (rate-limiting) step. This means that all mass transfer processes—both external and internal—must proceed significantly faster than the chemical reaction. In practical terms, this requires careful reactor design, appropriate choice of catalyst particle size, dilution with inert materials, and verification of the absence of mass transfer limitations. Failing to operate under reaction-controlled conditions can lead to over- or underestimation of the true catalytic activity and misleading conclusions about structure–activity relationships.

To determine whether external mass transfer limitations (related to steps 1 and 7) affect the observed reaction rate, a common approach is to vary the mass transfer coefficient by adjusting the superficial velocity of the reactants. Since the mass transfer coefficient depends on the Reynolds number (a dimensionless quantity that reflects flow characteristics and varies with flow rate), changing the superficial flow around the catalyst particles helps assess the influence of external transport on the reaction. To isolate this effect without altering the space velocity (defined as the ratio of volumetric (or molar) flow rate to catalyst volume or mass), the catalyst amount and flow rate are adjusted simultaneously to maintain constant space velocity while varying superficial velocity. This ensures that any observed changes in conversion are due to transport phenomena and not changes in residence time. Typically, an increase in flow rate (and thus in Reynolds number and the mass transfer coefficient) will lead to an increase in conversion if external mass transfer is limiting, as the film diffusion resistance is reduced. Once the mass transfer resistance becomes negligible, further increases in flow rate no longer affect the conversion, and the curve plateaus. This asymptotic behavior indicates the onset of the reaction-controlled regime Figure 4a. To ensure that the intrinsic kinetics are being measured, experiments should be conducted at reactant velocities in the plateau region, where external mass transfer is no longer rate-limiting.

To assess internal (intraparticle) mass transfer limitations, a common approach is to vary the catalyst particle size. Larger particles have longer diffusion paths, which can hinder the transport of reactants to active sites deep within the pores, resulting in artificially low observed reaction rates due to diffusion limitations. By systematically reducing the particle size while keeping other conditions constant (temperature, pressure, space velocity), one can observe whether the reaction rate increases (Figure 4b). If the rate becomes independent of particle size, it indicates that internal diffusion no longer limits the reaction, and the system is under kinetic control. This simple yet effective method helps ensure that measured reaction rates reflect the intrinsic catalytic activity, rather than transport constraints within the catalyst particles.

Figure 4. a) Flow Rate Test to assess the external mass transfer limitations, b) Particle Size Test to assess the internal mass transfer limitations, c) Arrhenius plot characterizing mass transfer-controlled and kinetic-controlled conditions.6

Even when catalyst particle size and reactant velocity are optimized to eliminate internal and external mass transfer limitations, this balance can shift with increasing reaction temperature. As temperature rises, the intrinsic reaction rate increases, often exponentially, according to the Arrhenius equation. At high enough temperatures, the rate of the chemical reaction may surpass the rates of mass transport, causing diffusion to become the rate-limiting step in the mechanism illustrated in Figure 3. To assess and manage this transition, one should analyze data using an Arrhenius plot, which displays the logarithm of the reaction rate versus the inverse of temperature (Figure 4c). In the low-temperature region, the slope corresponds to the true activation energy, indicating operation under kinetic control. However, as temperature increases, internal diffusion may no longer keep up with the reaction rate. In this intermediate region, the slope decreases, signaling that the process is entering a diffusion-limited regime. This behavior is quantitatively described by the effectiveness factor (η) and its relationship with the Thiele Modulus (ϕ), a dimensionless number that characterizes the relative importance of reaction kinetics and mass transfer limitations in a catalytic process. At low ϕ (kinetic regime), diffusion is fast relative to the reaction rate, and η approaches 1.0. Under strong internal diffusion limitations (large ϕ), η scales approximately as 1/ϕ, and the measured activation energy appears to be only half the true value. Similarly, the observed reaction order becomes approximately (n + 1)/2, where n is the true reaction order. At high temperatures, these limitations can become more pronounced, with external mass transfer increasingly dominating due to the accelerated reaction kinetics. Here, the slope in the Arrhenius plot (Figure 4c) no longer reflects reaction kinetics but rather the temperature dependence of the external mass transfer coefficient.

Figure 4. a) Flow Rate Test to assess the external mass transfer limitations, b) Particle Size Test to assess the internal mass transfer limitations, c) Arrhenius plot characterizing mass transfer-controlled and kinetic-controlled conditions.6

This analysis highlights the critical importance of conducting temperature-dependent kinetic studies while carefully interpreting Arrhenius plots. Neglecting mass transfer effects can lead to significant errors in characterizing both the intrinsic catalyst activity and the fundamental kinetic parameters of the reaction. Thus, it is essential to evaluate both internal and external mass transfer limitations under relevant reaction conditions to ensure accurate kinetic analysis. For a deeper understanding, one can refer to textbook definitions of Mears’ Criterion and Weisz-Prater Criterion for quantitatively assessing the external and internal mass transfer limitations, respectively.7

Another crucial consideration in assessing catalytic performance in a flow reactor is ensuring that all active sites within the catalyst bed are exposed to nearly identical reactant concentrations. This condition is not met at high conversions, where significant concentration gradients develop along the bed. For example, in a simplified A → B reaction operating at 90% conversion, the reactant concentration may drop from 100 mol at the inlet to 10 mol at the outlet. If the reaction follows first-order kinetics, the reaction rate at the top of the bed would be approximately ten times higher than at the bottom. Such a disparity leads to non-uniform reaction conditions, making it impossible to assign a single, representative rate value to the catalyst. To avoid this, kinetic measurements should be performed at very low conversions, typically below 2%, where the change in reactant concentration across the bed is negligible. These conditions are referred to as differential conversions. Under particularly constrained operating conditions, conversions up to 10% may still be considered near differential and can yield reasonably accurate estimates of intrinsic catalytic activity.

An added benefit of operating under differential conversions is the minimization of heat effects—reduced heat generation for exothermic reactions or reduced heat consumption for endothermic ones. This contributes to maintaining isothermal conditions within the reactor, which is essential for accurate kinetic measurements. Furthermore, operating at low conversions allows researchers to focus primarily on primary reactions—those that occur directly between the feed components.

This is particularly important in systems with complex reaction networks, where some products undergo secondary reactions to form new compounds. Since the formation of secondary products depends on the accumulation of primary products, studying the system at very low conversions helps isolate the intrinsic kinetics of the primary steps. To understand the full product distribution, however, it is good practice to carry out measurements across a wide range of space velocities (and thus conversions).

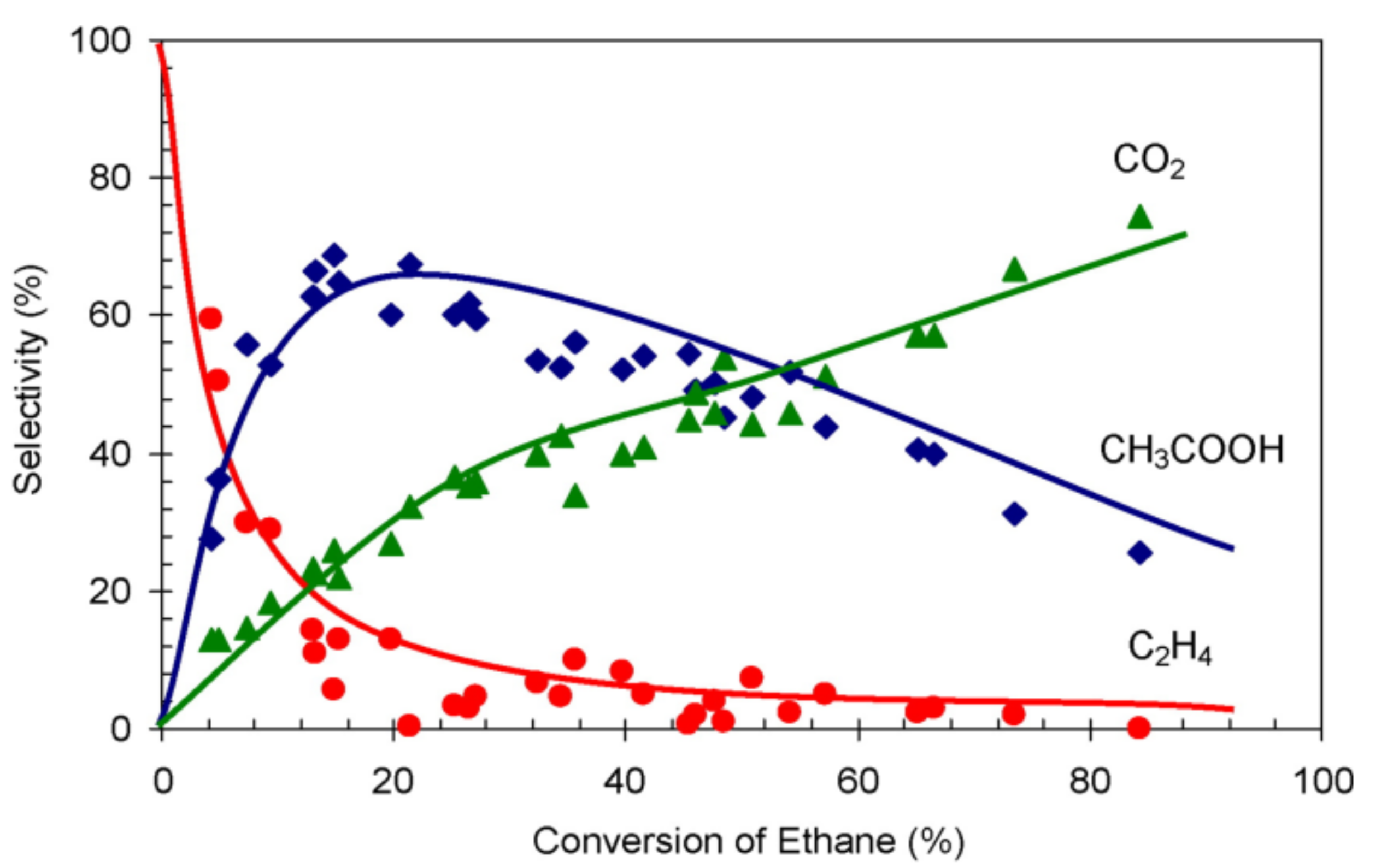

Figure 5. A representative illustration of the variation of product distribution with conversion.8

As illustrated in Figure 5, extrapolating product distribution data to zero conversion allows for the identification of primary products—those formed from the very first reactant molecules. The figure also demonstrates that product selectivity is stronglydependent on conversion. Therefore, reporting selectivity at a single conversion point can be misleading; a more informative approach is to present its variation across the entire conversion range.

In this context, the identification and quantification of every product molecule is critical. A key checkpoint for verifying this is the mass balance. Completing the mass balance is essential for accurately assessing catalytic performance, as it ensures that all inputs, outputs, and transformations within the reactor are accounted for. This enables evaluation of catalyst efficiency, reactant conversion, and the detection of product losses or side reactions. It also helps identify discrepancies in product quantification and supports the optimization of reaction conditions. Issues such as system leaks or measurement errors can be uncovered. As a best practice, the mass balance should close to at least 95% accuracy.

Equally important to accurate quantification is the careful choice of operating conditions, especially when evaluating catalyst stability over time. In some studies, researchers report stability at or near complete (100%) or equilibrium conversions. However, this approach can be misleading. At very low space velocities, the limiting conversion can be achieved using only the top portion of the catalyst bed. If that portion deactivates over time, subsequent layers of the catalyst may still maintain the same overall conversion, giving the false impression of sustained activity. This masking effect means that outlet conversion remains constant even as the catalyst is progressively deactivating. Therefore, the proper method for evaluating catalyst stability is to monitor time-on-stream performance at differential or sub-equilibrium conversions, where the full catalyst bed is actively contributing to the reaction (under near-identical conditions). Under these conditions, any loss in activity is directly reflected in the measured conversion. If deactivation is observed, the initial activity (i.e., performance at time zero) can be used for comparison with other catalysts, provided it is clearly stated that the reported value reflects initial rather than steady-state performance.

When comparing the performance of different catalysts, one of the most critical aspects is the unit in which catalytic activity is reported. Activity can be expressed per mass of catalyst, per mass or mole of metal, or ideally, per active site. Clearly specifying the basis of reported rates is essential for transparency and reproducibility. A common and acceptable unit is moles of reactant converted per gram of catalyst per unit time (e.g., mol g⁻¹ s⁻¹). However, a common mistake is to report rates using only inverse time units (e.g., h⁻¹) without specifying the quantities of reactant or catalyst involved—this makes the data ambiguous and incomparable.

While normalizing catalytic activity per gram of catalyst can be informative, it fails to account for differences in metal loading, dispersion, or the accessibility of active sites. For meaningful and rigorous comparisons, particularly in academic or high-impact publications, activity should instead be normalized to the number of active sites. This yields the turnover frequency (TOF), defined as the number of reactant molecules converted per active site per unit time. Reporting TOF is widely recognized as the best practice, as it reflects the intrinsic activity of the catalyst, independent of material quantity or reactor setup. Indeed, many leading catalysis journals now require TOF data as a condition for publication.

Once TOF becomes the benchmark, it naturally leads to deeper questions: What are the active sites? How many are present in a given catalyst? Addressing these questions requires accurate measurement of metal dispersion—the ratio of surface metal atoms to total metal atoms—which in turn demands a combination of advanced characterization techniques. Common methods include pulse chemisorption, controlled catalyst poisoning via precise inhibitor injection under reaction conditions, atomic-resolution electron microscopy, and synchrotron-based X-ray absorption spectroscopy to estimate active site populations. However, even with these powerful tools, further questions arise: Which specific surface species are truly responsible for catalytic activity? Can we distinguish active sites from spectator atoms? And critically, do these characterizations remain valid under actual reaction conditions, or does the catalyst restructure dynamically during operation? These challenges underscore the need for operando characterization, studying catalysts under realistic working conditions, which might be the topic of another note.

Ultimately, it is this pursuit of ever-deeper understanding that makes catalysis both demanding and intellectually rewarding. The more we learn, the more complex it becomes, which is exactly what makes it so fascinating!

Conclusions

Accurate assessment of catalytic performance in flow reactor systems demands careful control over experimental variables to ensure that observed reaction rates truly reflect intrinsic kinetics. By operating under differential conversions, minimizing heat and mass transfer limitations, and rigorously characterizing active sites, researchers can obtain meaningful and reproducible data. Adopting these best practices not only strengthens the reliability of kinetic measurements but also deepens our understanding of catalytic processes, laying the foundation for impactful discoveries in catalysis.

References

1. S. Çelebi, N. Bağlar, E. Kocaman, A. Uzun, Ö.D. Bozkurt, Ö. Akarçay, “Gliserinin eterifikasyonu için bir sistem ve yöntem-A system and method for glycerine etherification,” Turkish Patent Institute Patent 2016/17804.

2. J. R. Anderson, "Some remarks on the design of catalytic reactors," Chemical Engineering Science, 1975, 30(7), 917–923.

3. G. Behrendt, B. Mockenhaupt, N. Prinz, M. Zobel, E.-J. Ras, M. Behrens, “CO Hydrogenation to Methanol over Cu/MgO Catalysts and Their Synthesis from Amorphous Magnesian Georgeite Precursors,” ChemCatChem, 2022, 14, e202200299,

4. E. Millán, N. Mota, R. Guil-López, B. Pawelec, J. L. García Fierro, R.M. Navarro, “Direct Synthesis of Dimethyl Ether from Syngas on Bifunctional Hybrid Catalysts Based on Supported H3PW12O40 and Cu-ZnO(Al): Effect of Heteropolyacid Loading on Hybrid Structure and Catalytic Activity,” Catalysts, 2020, 10(9), 1071.

5. https://www.training.itservices.manchester.ac.uk/public/gced/reactors.html?reactors/external_mass_rate/index.html, last accessed on May 16, 2025.

6. M. Zhang, M. Wang, B. Xu, D. Ma, “How to Measure the Reaction Performance of Heterogeneous Catalytic Reactions Reliably,” Joule, 2019, 3, 2871–2883.

7. H. S. Fogler, “Elements of Chemical Reaction Engineering (5th Edition),” Prentice Hall, Boston, 2016.

8. F. Rahman, K.F. Loughlin, M.A. Al-Saleh, M.R. Saeed, N.M. Tukur, M.M. Hossain, K. Karim, A. Mamedov, “Kinetics and mechanism of partial oxidation of ethane to ethylene and acetic acid over MoV type catalysts,” Applied Catalysis A: General, 2010, 375, 17–25.

An overview of CO2 hydrogenation to produce fuels and chemicals

By Dr. Merve Doğan Özcan

1. Introduction

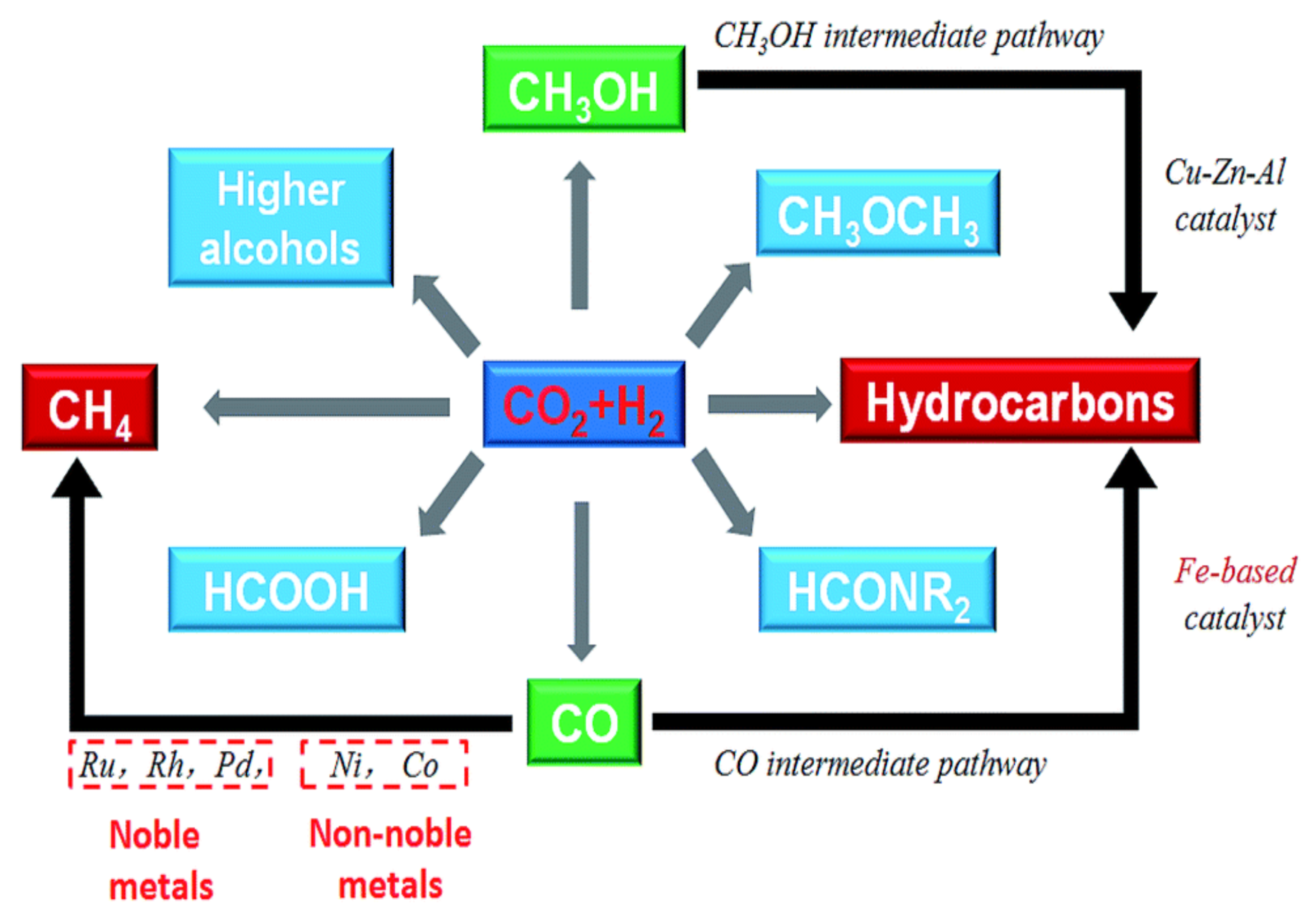

Global warming poses a significant threat to human survival and sustainable development, representing an urgent global challenge requiring immediate attention. Addressing climate change is not only a critical environmental priority but also a strategic objective necessary to achieve coordinated and sustainable socio-economic progress. Among the various greenhouse gases, carbon dioxide (CO2) is one of the most prevalent and long-lived in the atmosphere, exerting a substantial influence on the greenhouse effect [1]. The majority of anthropogenic CO2 emissions originate from industrial and energy-related activities. The continuous rise in atmospheric CO2 concentrations contributes directly to enhanced greenhouse warming, ocean acidification, sea-level rise, and increased frequency of extreme weather events. Consequently, developing effective strategies for the utilization and conversion of CO2 is crucial for the transition toward a resource-efficient and environmentally responsible society. CO2 reutilization is a pivotal step in realizing a sustainable carbon cycle aligned with human needs [2]. CO2 serves as a fundamental C1 source, and its conversion typically follows three principal pathways: (1) dry reforming with methane (CH4) to produce synthesis gas (syngas), (2) conversion into fuels via electrochemical, photochemical, or thermochemical methods, and (3) catalytic hydrogenation to produce value-added chemicals including lower olefins, higher hydrocarbons, formic acid, methanol, and higher alcohols (Figure 1). These conversion technologies facilitate carbon recycling, mitigate fossil fuel dependence, and reduce the environmental burden of CO2 emissions. Among these, CO2 hydrogenation stands out as a practical and scalable solution for carbon valorization [3].

From a molecular perspective, CO2 consists of a linear O=C=O structure with a bond angle of 180°. The molecule features two σ bonds formed by the overlap of carbon's sp hybrid orbitals with the oxygen atoms, while the p orbitals form two π bonds. Due to its strong C=O bond (dissociation energy ~750 kJ/mol), CO2 exhibits considerable thermodynamic stability and chemical inertness. Effective conversion thus requires a reducing agent with more negative Gibbs free energy, typically hydrogen (H2), and the presence of a catalyst to lower the activation energy of reaction intermediates. Elevated temperature and pressure conditions are often necessary to achieve satisfactory conversion rates. Hydrogenation of CO2 can yield various products, including CO, CH4, and methanol (CH3OH). This process, known as CO2 hydrogenation, is one of the most promising thermal catalytic approaches for CO2 reduction [4].

Figure 1. Conversion of CO2 to chemicals and fuels through hydrogenation [3].

2. CO2 Hydrogenation to Methane

CO2 can also serve as a chemical energy carrier, enabling the transformation of intermittent renewable energy into storable fuels. The hydrogenation of CO2 into methane, in particular, is a viable route for energy storage and decarbonization. Electrolytic generation of H₂ from water using renewable energy can be integrated with CO2 methanation to form a closed-loop carbon cycle, enhancing the feasibility of large-scale energy storage. Nevertheless, renewable energy systems are inherently intermittent, necessitating scalable and efficient storage solutions [5]. The production of synthetic natural gas via CO2 methanation, known as the “Power-to-Gas” (PtG) concept (Figure 2), has gained significant interest. In this process, CO2 reacts with H₂-produced via water electrolysis powered by wind or solar energy to form CH₄, a direct substitute for natural gas. A notable example is the commercial-scale PtG facility established in Copenhagen in 2016 with a capacity of 1.0 MW. Between 2009 and 2013, several pilot and commercial scale methanation projects were conducted in Germany, with capacities ranging from 25 kW to 6.3 MW. The Sabatier reaction, first reported by Paul Sabatier in 1902, underpins these efforts. Owing to its high selectivity (up to 99% CH4) and thermodynamic favorability between 25°C and 400°C, CO2 methanation remains a cornerstone for renewable energy integration and greenhouse gas mitigation [3].

Figure 2. Schematic illustration of CO2-based sustainable production of chemicals and fuels [3].

Transition metals such as Ni, Co, Ru, Rh, and Pd are effective catalysts for this reaction. Among them, Ni-based catalysts are most commonly employed due to their high activity, methane selectivity, low cost, and industrial scalability. The catalytic activity generally follows the order: Ru > Rh > Ni > Co > Pt > Pd. Among the various metal oxide supports, such as TiO₂, SiO₂, Al₂O₃, CeO₂, and ZrO₂, alumina and titania supported catalysts have demonstrated notably high activity and selectivity for methane production, making them a focal point of extensive research. It has been well established that metal-support interactions can substantially alter the properties of the active metal phase, particularly its morphology and dispersion, which in turn influence the catalytic performance in CO2 hydrogenation reactions. In addition, both the metal loading and the crystallite size are key factors affecting catalytic activity, with their impact being strongly contingent upon the specific metal-support combination and the operational conditions utilized [6].

3. CO₂ Hydrogenation to Methanol

Methanol synthesis from CO2 hydrogenation is a promising approach within the "methanol economy" framework, proposed by George A. Olah in 2005. This process not only captures and recycles CO2 but also provides a sustainable route to produce methanol, a versatile platform chemical. Historically, methanol was first observed by Robert Boyle in 1661 and industrialized by BASF in 1923 using Cu/ZnO/Cr₂O₃ catalysts. Today, methanol production typically involves a mixture of syngas (CO + H₂) and CO2. Although syngas routes are well-established, they suffer from high energy demands and limited stability. Direct hydrogenation of CO2 is therefore gaining attention as a more sustainable alternative. CO2 hydrogenation to methanol is exothermic, while the competing reverse water-gas shift (RWGS) reaction is endothermic. Consequently, low temperatures and high pressures favor methanol formation. Activation of the stable CO2 molecule typically requires reaction temperatures above 240°C, but excessively high temperatures promote CO formation over methanol. Elevated pressures also suppress the RWGS reaction and enhance methanol yields. The optimal H2:CO2 ratio is approximately 3:1 [4,7].

Key reactions [8]:

CO₂ + 3H₂ → CH₃OH + H₂O ΔH = –49.5 kJ/mol

CO₂ + H₂ → CO + H₂O ΔH = +41.2 kJ/mol

Research in this domain focuses on improving catalytic efficiency, selectivity, and stability. Cu-based catalysts are widely studied due to their affordability and favorable performance. However, single-component Cu catalysts often exhibit limited activity, necessitating the use of supports and promoters to enhance performance [9]. Cu/ZnO/Al₂O₃ is a well-established commercial catalyst widely used for methanol synthesis. In this system, ZnO functions not only as conventional support but also as a promoter for Cu-based catalysts. Specifically, ZnO acts as a geometric spacer between Cu nanoparticles, enhancing their dispersion and increasing the exposure of catalytically active Cu surface sites. Additionally, ZnO modifies the electronic properties of the catalyst through metal-support interactions. The inclusion of Al₂O₃, known for its high thermal stability, further serves as a structural promoter by inhibiting the sintering and agglomeration of active metal particles under reaction conditions [4]. Recent developments include bimetallic systems (e.g., Cu-Zn, Pd-Zn, Cu-Ni) and novel materials like metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) [10], which provide enhanced catalytic control and adaptability to varying conditions.

4. CO2 Hydrogenation to C2+ Hydrocarbons

The conversion of CO2 to longer-chain hydrocarbons (C2+) is particularly attractive due to their higher energy densities and broad applicability as fuels and chemical feedstocks. Conventional hydrocarbon synthesis from CO relies on the Fischer–Tropsch synthesis (FTS). But replacing CO with CO2 introduces thermodynamic and kinetic challenges, primarily due to CO2’s inertness and its tendency to undergo methanation [11]. CO2 hydrogenation to hydrocarbons can follow either direct or indirect pathways, including routes via the RWGS and FTS reactions or through methanol as an intermediate. Due to kinetic challenges in direct conversion, recent efforts have focused on a modified FTS approach, particularly using iron-based catalysts known for enhancing C–C coupling [12]. A key discovery in 1978 [13] revealed that CO2 affects product distribution in FTS, prompting further catalyst development. Although FTS kinetics are less favorable than those of RWGS, the chemical similarity between CO and CO2 continues to support the use of Fe catalysts in hydrocarbon synthesis from CO2.

Relevant reactions:

CO2 hydrogenation: nCO₂ + 3nH₂ → (1/4) CₙH₂ₙ + 2nH₂O ΔH = –128 kJ/mol

RWGS: CO₂ + H₂ → CO + H₂O ΔH = +38 kJ/mol

FTS: 2nCO + (3n + 2)H₂ → 2CₙH₂ₙ₊₂ + 2nH₂O ΔH = –166 kJ/mol

Recent breakthroughs have demonstrated that methanol can serve as an effective intermediate in the indirect CO2 hydrogenation to long-chain hydrocarbons, offering an alternative to traditional pathways. Unlike the Fischer–Tropsch synthesis (FTS), which typically follows the Anderson–Schulz–Flory (ASF) distribution and limits the selectivity of gasoline- and diesel-range hydrocarbons, the methanol-mediated route has the potential to overcome these limitations. Although CO2 and CO hydrogenation via methanol differ in aspects such as molecular polarity and adsorption behavior, they share common downstream processes, like methanol conversion over zeolites. This similarity suggests that catalyst designs from syngas conversion could inform the development of bifunctional catalysts for CO2 hydrogenation, as recent advances have shown the ability to selectively produce desired hydrocarbons beyond ASF constraints [14].

5. Conclusion

The catalytic hydrogenation of CO2 into methane, methanol, and C2+ hydrocarbons offers viable pathways to mitigate climate change while facilitating energy storage and chemical production. Key to advancing these technologies are the development of highly efficient and selective catalysts, optimization of reaction conditions, and integration with renewable energy sources. Continued research into catalyst design-including bimetallic systems, supports, and bifunctional materials will be essential for scaling CO2 utilization technologies and achieving a carbon-neutral future.

6. References

[1] Cui Z, Meng S, Yi Y, Jafarzadeh A, Li S, Neyts EC, et al. Plasma-Catalytic Methanol Synthesis from CO2Hydrogenation over a Supported Cu Cluster Catalyst: Insights into the Reaction Mechanism. ACS Catal 2022;12:1326–37. https://doi.org/10.1021/acscatal.1c04678.

[2] Vourros A, Garagounis I, Kyriakou V, Carabineiro SAC, Maldonado-Hódar FJ, Marnellos GE, et al. Carbon dioxide hydrogenation over supported Au nanoparticles: Effect of the support. J CO2 Util 2017;19:247–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcou.2017.04.005.

[3] Li W, Wang H, Jiang X, Zhu J, Liu Z, Guo X, et al. A short review of recent advances in CO2 hydrogenation to hydrocarbons over heterogeneous catalysts. RSC Adv 2018;8:7651–69. https://doi.org/10.1039/c7ra13546g.

[4] Liu X, Zhang H, Du J, Liao J. Research progress of methanol production via CO2 hydrogenation: Mechanism and catalysts. Process Saf Environ Prot 2024;189:1071–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psep.2024.07.018.

[5] Duyar MS, Ramachandran A, Wang C, Farrauto RJ. Kinetics of CO2 methanation over Ru/γ-Al2O3 and implications for renewable energy storage applications. J CO2 Util 2015;12:27–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcou.2015.10.003.

[6] Panagiotopoulou P. Hydrogenation of CO2 over supported noble metal catalysts. Appl Catal A Gen 2017;542:63–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcata.2017.05.026.

[7] Jiang X, Nie X, Guo X, Song C, Chen JG. Recent Advances in Carbon Dioxide Hydrogenation to Methanol via Heterogeneous Catalysis. Chem Rev 2020;120:7984–8034. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00723.

[8] Choi EJ, Lee YH, Lee DW, Moon DJ, Lee KY. Hydrogenation of CO2 to methanol over Pd–Cu/CeO2 catalysts. Mol Catal 2017;434:146–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcat.2017.02.005.

[9] Phongamwong T, Chantaprasertporn U, Witoon T, Numpilai T, Poo-arporn Y, Limphirat W, et al. CO2 hydrogenation to methanol over CuO–ZnO–ZrO2–SiO2 catalysts: Effects of SiO2 contents. Chem Eng J 2017;316:692–703. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2017.02.010.

[10] Mazari SA, Hossain N, Basirun WJ, Mubarak NM, Abro R, Sabzoi N, et al. An overview of catalytic conversion of CO2 into fuels and chemicals using metal organic frameworks. Process Saf Environ Prot 2021;149:67–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psep.2020.10.025.

[11] Muleja AA, Yao Y, Glasser D, Hildebrandt D. Variation of the short-chain paraffin and olefin formation rates with time for a cobalt Fischer-Tropsch catalyst. Ind Eng Chem Res 2017;56:469–78. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.iecr.6b03512.

[12] Nie X, Wang H, Janik MJ, Chen Y, Guo X, Song C. Subscriber access provided by UNIV OF ARIZONA Mechanistic Insight Into C-C Coupling over Fe-Cu Bimetallic Catalysts in CO 2 Hydrogenation. J Phys Chem C, Just Accept Manuscr • Publ Date 2017:25.

[13] Dwyer DJ, Somorjai GA. Hydrogenation of CO and CO2 over iron foils. Correlations of rate, product distribution, and surface composition. J Catal 1978;52:291–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-9517(78)90143-4.

[14] Cheng K, Gu B, Liu X, Kang J, Zhang Q, Wang Y. Direct and Highly Selective Conversion of Synthesis Gas into Lower Olefins: Design of a Bifunctional Catalyst Combining Methanol Synthesis and Carbon-Carbon Coupling. Angew Chemie - Int Ed 2016;55:4725–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201601208.

PhD Stories

By Dr. Nurbanu Çakıryılmaz Şahingöz

Hello, I am Nurbanu Çakıryılmaz Şahingöz. In 2025, quite recently 😊, I received my Ph.D. degree from the Department of Chemical Engineering at Gazi University. For about two years, I have been working at Roketsan Inc., and I am one of those who manage an academic and professional career together.

My doctoral research focused on the production of hydrogen-rich gas mixtures through the steam reforming of diesel. Within this scope, I carried out catalyst design and reactor modeling studies. During my undergraduate education, my career goal was to stay in academia and become a faculty member. Therefore, after completing my master's degree, I immediately started my Ph.D without a break. However, life opened completely different doors for me. Thus, I drew my own path by merging academia with the private sector.

While working at my first workplace, LENTATEK UZAY HAVACILIK and TEKNOLOJI Inc., I simultaneously completed my doctoral lectures. Thanks to the company's support for academic development, my course period was relatively smooth until the Ph.D. qualifying exam. The difficulty of the private sector started here. I would work during the day and study for my qualifying exam with whatever energy I had left in the evenings. This process was quite arduous for me. It is really hard to describe in words the happiness I felt after passing the qualifying exam after months of hard work.

The most enjoyable part of my Ph.D. was being able to conduct extensive experimental work. After passing the qualifying exam, I combined my professional project with my thesis topic, which allowed me to work with great motivation for about a year and a half. However, when the project, I was assigned, was canceled, all plans were turned upside down. I had to change my thesis topic and start over from scratch.

In the midst of this challenging period, motherhood entered my life. It seemed almost impossible to manage the roles of work, academic career and motherhood at the same time, and I seriously considered quitting my Ph.D. studies. She was my advisor, Prof. Dr. Nuray Oktar who had successfully balanced both academia and motherhood that inspired me to continue. Thanks to her encouraging support, I persevered my Ph.D. With luck on my side, a new project arrived at my former workplace, and with intense effort, I was able to complete the experimental studies for my thesis. Being able to turn a project, you work, into a thesis provides a great advantage; however, it always brings some risks. I can say that “there's no rose without a thorn” summarizes this process exactly.

Throughout this up and down journey, developing a prototype and a catalyst that met the needs of the private sector has been a great source of pride for me. I am grateful for having specialized in my field, learned from my mistakes, and advanced stronger in my career while continuously learning and improving myself. Despite the blood, sweat, and tears, the sense of accomplishment I gained at the end made every moment worth it.

Moving forward, my career goal is to contribute to my country’s advancement in the defense industry by developing new products as a Ph.D. design engineer.

Recent Selected Papers in Our Catalysis Community

In recent months, there have been exciting research studies in catalysis research in Turkey. Here are the short summaries:

Gas Separation and Machine Learning-Assisted Materials Engineering

Habib, N., Gulbalkan, H. C., Aydogdu, A. S., Uzun, A., Keskin, S. (2025). Toward rational design of ionic liquid/Metal-Organic Framework composites for efficient gas separations: Combining molecular modeling, machine learning, and experiments to move beyond trial-and-error. Coordination Chemistry Reviews, 539, 216707.

This review explores the promising field of ionic liquid/metal-organic framework (IL/MOF) composites, which combine the tunable properties of ionic liquids with the high porosity of MOFs to improve gas adsorption and separation, especially for CO₂ capture. It highlights advancements in synthesis methods and the development of mixed matrix membranes with enhanced performance, while noting the current reliance on trial-and-error in material design. The review also emphasizes the growing role of computational tools and machine learning in accelerating the discovery and optimization of IL/MOF composites for next-generation gas separation technologies.

Sustainable Materials

García-González, C. A., Blanco-Vales, M., Barros, J., Boccia, A. C., Budtova, T., Durãe, L., Erkey, C., Gallo, M., Herman, Kalmár, P. J., Iglesias-Mejuto, A., Malfait, W. J., Zhao, S., Manzocc, L., Plazzotta, S., Milovanovic, S., Neagu, M., Nita, L. E., Paraskevopoulou, P., Roig, A., Simón-Vázquez, R., Smirnova, I., Tomović, Ž., López-Iglesias, C. (2025). Review and Perspectives on the Sustainability of Organic Aerogels. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng, https://doi.org/10.1021/acssuschemeng.4c09747.

Aerogels are ultra-light materials with high porosity and surface area, offering promising solutions in industries like construction and energy storage due to their sustainability potential. This review explores recent developments in organic and hybrid aerogels, emphasizing their alignment with the UN Sustainable Development Goals and proposing strategies to enhance their eco-friendliness, including the use of biopolymers and recycling methods. It also stresses the importance of life cycle assessments and safety evaluations to support a circular economy and maximize the sustainable impact of aerogels.

Gas Separation

Yousefzadeh, H., Yurdusen, A., Tüte, A., Aksu, G. O., Mouchaham, G., Keskin, S., Serre, C., Erkey, C. (2025). Calcium Alginate Aerogel-MIL160 Nanocomposites for CO2 Removal. Langmuir, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.langmuir.5c00143.

Using MOF/aerogel composites (MOFACs) in bead form can overcome the pressure drop and mass transfer issues seen with powdered MOFs, without sacrificing adsorption performance. In this study, Ca-alginate aerogel–MIL-160(Al) composites were synthesized and showed preserved MOF structure, enhanced CO₂ uptake, and improved CO₂/N₂ selectivity compared to pure MOFs. The results demonstrated strong static and dynamic CO₂ adsorption performance, making these MOFACs promising candidates for efficient gas adsorption applications.

Biodiesel Production

Çakırca, E. E., Akın, A. N. (2025). Parametric Study of Biodiesel Synthesis from Waste Cooking Oil Using Ca-Rich Mixed Metal Oxides. ACS Omega, 10, 17907−17916.

This study explores biodiesel production from waste cooking oil (WCO) using calcium-containing mixed metal oxide catalysts, particularly CaAl hydrotalcite-like structures, due to their reusability and environmental benefits. Optimal reaction conditions (338 K, 6:1 methanol-to-WCO ratio, 3% catalyst, 5 hours) resulted in a 96% FAME yield, meeting the EN 14214 biodiesel standard. While the CaAl catalyst remained effective after four cycles, it eventually began dissolving in the reaction medium, affecting long-term reusability.

Photocatalysis

Nejatpour, M., Yılmaz, B., Ozden, B., Barisci, S., Dükkancı, M. (2025). The function of carbon quantum dots (CQDs) derived from peapod biomass in composite photocatalysts for the enhanced photodegradation of perfluoroalkyl carboxylic acids (PFCAs) under UVC and visible light irradiation. Journal of Water Process Engineering, 73,107750.

This study developed a sustainable carbon quantum dot (CQD)/TiO₂ composite photocatalyst from peapod biomass to enhance the degradation of persistent perfluoroalkyl carboxylic acids (PFCAs). The composite significantly outperformed pure TiO₂ in degrading both long-chain (e.g., PFOA) and short-chain PFCAs under UVC and visible light, achieving notable improvements in degradation rates and defluorination efficiency. These findings highlight the promise of CQD/TiO₂ photocatalysts for effective and environmentally friendly PFCA remediation.

Hydrogen/Syngas Production

Sarıyer, M., Doğu, T., Sezgi, N. A. (2025). Microwave-heated carbon-coated monolithic reactor for steam reforming of ethanol. Chemical Engineering Journal, 512, 162398.

A microwave-heated carbon-coated monolithic reactor was developed to improve efficiency and environmental performance in hydrogen production via ethanol steam reforming. Compared to conventional systems, the microwave-heated reactor demonstrated significantly higher hydrogen yield and purity, particularly at lower temperatures like 400 °C. The monolithic structure and volumetric heating reduced coke formation by minimizing the Bouduard reaction, enhancing catalytic activity and system durability.

Syngas Production and Machine Learning

Coşgun, A., Günay, M. E., Yıldırım, R (2025). Explainable machine learning analysis of tri-reforming of biogas for sustainable syngas production. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, Volume 127, 595-607.

This study applied machine learning techniques to analyze tri-reforming of biogas using a dataset of 1183 entries from 29 studies, focusing on CH₄ conversion, CO₂ conversion, and H₂/CO ratio. Random forest models showed strong predictive performance, particularly for CH₄ and CO₂ conversions, and SHAP analysis identified reaction temperature as the most influential factor for CH₄ conversion. Decision tree classification further enhanced model explainability by generating heuristic rules that link specific descriptor combinations to different performance outcomes.

Selections from the Catalytic Wisdom Guide

Previous issue answers Newsletter #13:

1. KARGEL, 2. Autothermal, 3. TUPRAŞ, 4. Hydrogen, 5. Glycerol, 6. Electrolysis, 7. Sivas, 8. Biomass, 9. SESAME

Announcements

In 2025, there will be a highly active program of events in the field of catalysis.

• From June 25 to 28, 10th National Catalysis Conference (NCC10), organized by the Catalysis Society and Cumhuriyet University, will take place in Sivas. We look forward to welcoming you there.

• From July 9 to 11, The 14th International Symposium of the Romanian Catalysis Society (RomCat 2025), organized by Societatea De Cataliza Din Romania will be held on Gluj-Napoca, Romania. For more information: http://www.unibuc.ro/romcat/

• From August 31 to September 5, 16th Europacat Conference, organized by EFCATS, of which our society is a member, will be held in Trondheim, Norway.

• From September 1 to 4, 36th National Chemistry Congress, organized by Van Yüzüncü Yıl University will feature a "Catalysis" session supported by Catalysis society."

• From September 9 to 12, the 16th National Chemical Engineering Congress, organized by Bolu Abant İzzet Baysal University, will host a special session on "Catalysis and Reaction Engineering," supported by Catalysis society.