Dear Catalysis Researchers,

Welcome to the 12th edition of Magic Powder from Catalysis Society.

This issue highlights groundbreaking advancements in catalysis, driven by the transformative power of machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI), while celebrating the human stories behind the science.

At the heart of this edition is a comprehensive exploration of “Machine Learning for Catalysis” by Prof. Dr. Ramazan Yildirim, who delves into how ML algorithms are revolutionizing catalyst design—accelerating discovery, optimizing performance, and bridging molecular insights with macroscopic outcomes. Complementing this, our feature on the “Solar Energy, Catalysis, and Machine Learning Laboratory” showcases cutting-edge research in renewable energy technologies, from photocatalytic hydrogen production to CO₂ reduction, underpinned by robust experimental and computational frameworks. In “PhD Stories”, Dr. Orhan Özcan offers a heartfelt narrative of resilience and discovery, reminding us that scientific breakthroughs are often born from persistence and collaboration.

Meanwhile, our Recent Selected Papers section spotlights Turkish researchers’ contributions to photocatalysis, hydrogen production, and sustainable waste valorization, underscoring the global impact of local innovations. A highlight of this issue is the upcoming *10th National Catalysis Conference (NCC10)*, set to take place from June 25 to 28, 2025, in Sivas, Turkey. Organized by the Catalysis Society and Cumhuriyet University, NCC10 promises to be a cornerstone event for catalysis researchers, featuring plenary lectures by globally renowned scientists, and sessions on topics ranging from heterogeneous and homogeneous catalysis to sustainable and unconventional catalytic processes. This conference will not only provide a platform for knowledge exchange but also foster collaborations that drive the future of catalysis research.

In this edition, also engage your curiosity with our *Crossword Puzzle* by Prof. Merlin Catalystorius, and mark your calendars for pivotal events like NCC10 and other international scientific activities detailed in our announcements.

As catalysis continues to shape a cleaner, more efficient future, Magic Powder remains your gateway to knowledge, inspiration, and connection. Together, we break barriers—one reaction at a time. For more updates, insights, and exclusive content, visit our *Magic Powder Blogger Page*: [https://magicpowder2024.blogspot.com/p/magic-powder-scientific-monthly.html] which also involves podcasts.

To stay connected and receive our monthly newsletter directly in your inbox, subscribe via email at *magicpowder2024@gmail.com*.

Join us as we continue to explore the fascinating world of catalysis and its transformative potential!

Catalysis Society

Editorial Board

Prof. Dr. Ayşe Nilgün AKIN

Prof. Dr. N. Alper TAPAN

Dr. Merve DOĞAN ÖZCAN Asst. Prof. Dr. Elif CAN ÖZCAN

Dr. Mustafa Yasin ASLAN

Machine Learning for Catalysis

Ramazan Yıldırım

Department of Chemical Engineering, Boğaziçi University, 34342, Bebek-Istanbul

E-mail: yildirra@bogazici.edu.tr

Introduction

Catalyst development is a costly and exhausting work involving the optimization of numerous variables including the material type (support, active metal promoter) and composition, procedure and parameters used for synthesis (precursors, solvents, pH, temperature, time), pretreatment (calcination and reduction) and operational conditions (temperature, pressure, feed composition, space velocity and so on). Even if we take the catalyst properties only, we can see a complex multi-level network of interacting variables from the molecular properties (HOMO/LUMO energies, band gap, binding energy, charge, crystal structure etc.) to macroscopic properties (surface area, particle size, pore size, surface acidity, dispersion etc.) of actual catalyst and catalytic performance (turnover frequency, conversion, selectivity, yield, stability and so on), which are not straightforward either. On the other hand, the need of more effective new catalysts is increasing continuously with the increasing demand for more efficient, environmentally friendly and healthy products and processes. Hence, the use of new tools like machine learning (ML) is required to improve catalyst design process in terms of effectiveness, cost, and speed. Indeed, astonishing developments in hardware, software code and accessibility of large amount of data accumulated in databases, publications and other digital sources have made ML applications much easier and more effective in many fields including catalysis in recent years.

As a branch of artificial intelligence, ML is a science of creating and optimizing computer programs that can learn from the data; it relies on statistical learning using some specially designed algorithms. These programs can be used to perform various tasks such as identifying hidden patterns, making generalizable rules or constructing models to be used for the prediction of the outcome of unexplored conditions. Generative AI tools, which have been developed in the last few years, can even perform human like inference function and create their own outcome and content.

In this paper, we will briefly summarize the past developments in ML applications in catalysis, discuss the current state of art with examples, and provide a perspective for long term developments and the challenges to be overcome.

The past

Some of the ML tools like artificial neural networks, decision trees, support vector machines have been used for long time, without referring ML, as this concept was popularized in last two decades. For example, Zupan and Gasteiger published an article reviewing the applications of artificial neural networks in the field of chemistry in 1991 and 1993 [1-2]. Burns and Whitesides, in 1993, also reviewed early applications of ANN concluding that this technique can be used for well-defined but poorly understood data such as spectroscopy, sensor readings and biological sequences [3]. The first review article in ANN applications in chemical engineering was also published by Himmelblau in 2000 [4]. Similarly, decision trees have been also used in chemistry/chemical engineering related areas since 1970s; examples are the classification of petroleum pollutants [5], classification of octane numbers of hydrocarbons [6], and classification of the color of Barbaresco wine samples [7].

The applications of ML tools (again without referring ML) in catalysis and photocatalysis have also appeared since the mid-1990s [8]. Since then, ML has been implemented in various reactions including epoxidation of large olefins [9], steam reforming CH4 [10-11], dry reforming of CH4 [12], selective CO oxidation [13], water gas shift reaction [14], transesterification of triglycerides [15], CO2 and electrochemical reduction of CO2 [16].

The initial ML applications in catalysis, as in any other field, have involved its use for relatively small datasets created in the same laboratory; however, it has been transformed into something bigger in many respects starting early 2000s. While the variety of data sources (mostly digital and online) as well as the size and complexity of the dataset have been growing, the ML algorithms has been also getting more effective; meanwhile, the ML works or project was turned from the simple application of single algorithm to a holistic framework including the use of multiple algorithms as well as additional steps before and after the running of ML algorithm. It appears that we are witnessing a similar (probably bigger) transformation today with the emergence of generative AI tools as we will discuss later.

The present

Current state of art in ML

In current practice, ML is generally implemented through a framework containing various steps from data generation to interpretation of results as described in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Implementation steps of ML

As the first step, we need a dataset relating the input variables, which may be also called as descriptors, features and fingerprints (like properties of catalytic materials and reaction system and conditions including feed) to response (or output) variable, which may be other properties or function of material (like surface area) or performance described in various ways (conversion, selectivity, yield, stability etc.). Both input and output variables may be categorical (like material type) or continuous (like temperature), they may be set by the user (like intended active metal loading) or measured (like actual active metal loading measured); similarly, it may be real or derived from the others (like principal components). Ward et al. reported in their publication that they identified 148 candidates to describe a material; they group them as stoichiometric attributes, elemental property statistics, electronic structure attributes, and ionic compound attributes) [17]. Obviously, there is no way to determine the values of these variables for every experimental (and even computational) data point. We need to determine a reasonable number of input variables that is sufficient to describe the output (that is why we also call the input variables as descriptors). The data may be experimental or computational or combining both; it may be generated in-house or extracted from external sources like databases and past publications. In recent years, data extraction from external sources became a very attractive means of constructing dataset thanks to the databases like Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) [18], Cambridge Structural Database [19], The Material Project [20], and Novel Materials Discovery (NOMAD) Repository [21]. It is also possible to extract data from published sources as we have been done in recent years [22].

Data pre-processing refers to the activities carried out before the model construction to organize the data in a machine-readable format while completing the missing information by imputing the data in a suitable way such as taking the mean or mode, determining by using similarities with known cases or creating using creating other tools. Then, the data processed further (like normalization, standardization and transformation) to make it more suitable for ML analysis. Lastly, the input variables are finalized by checking the cross correlations and analyzing their relative significance [23]; this is also called feature engineering to underline the importance of having a right set of descriptors. Dimensionality reduction is another related concept pointing out that the number of descriptors should be as small as possible for a given dataset to obtain a robust model; this is achieved either by feature selection (decreasing the number of descriptors using some tools like Boruta analysis) or by feature extraction, (creating smaller number of new descriptors, like principal components) from the original set.

Then one can select the suitable ML algorithm considering the knowledge to be extracted and structure of data. The ML algorithms can be grouped according to their functions such as description (exploratory data analysis), clustering, classification, estimation/prediction, and association [24-25]. Exploratory data analysis aims to analyze the data using some descriptive statistics while the clustering groups the data using the similarity in features; both are used as pre-analysis tools before the ML model is constructed. On the other hand, classification groups the data in terms of range or categories of the output variables; as expected, estimation/prediction, as the most common task in ML, is used to construct models to predict the outcome of unknown conditions. Finally, association rule mining (ARM) is utilized to determine the hidden relations among the features, including output [25]. As we also mentioned in Introduction (and will discuss in detail later), we can also add inference capabilities of newly popularized generative AI tools to the list of functions that can be performed.

Finaly a model can be constructed using the complete dataset with final descriptor and selected algorithms. In practice, the model building represents training the model with the data (i.e. determine the optimum model hyperparameters representing the data best). The common practice in model building starts with division of data into training (large portion as 70-80%) and testing (remaining data) randomly. Then, ML model is trained using the training set by often utilizing a procedure called k-fold cross-validation: divide the training data into k fold and use k-1 fold to train the data and remaining fold for validation by repeating the procedure k times by switching the validation. This procedure is repeated various values of hyperparameters, and values resulting in the minimum average (of k folds) validation error are chosen as the optimum model, which has to pass the final test using the testing set separated at the beginning of training. The model building is usually followed by interpretation (for example, analyzing the importance of input variables) and utilization of the model.

Figure 2. Basic tasks and algorithms of ML [26]

Current ML applications in catalysis

We discuss the basic characteristics of historical and current applications of ML with examples in Section 2. More detailed discussions for specific examples can be seen in numerous review articles published in recent years [22, 27-30]. Here, we will focus on the need of work to be done to improve the catalysis design and development and assess the current state of applications with this perspective; this way we can better assess the contribution of works that have been performed so far and the challenges we are facing. As presented in Figure 3, the contribution of ML in catalysis research can be evaluated in four categories: (1) Discovering/identifying the suitable catalytic materials, (2) estimation of relevant microscopic and macroscopic properties, (3) determining the mechanisms and developing kinetic models, and (4) analyzing the results of performance test.

The use of ML for the discovery of new material is one of the most common applications in material science in recent years. The process generally relies on multistep screening of a very large number of unknown materials (real or virtual) using ML models trained with relatively smaller number of materials with known molecular properties; this way the pool of potential candidates is reduced to a size that can be studies in more detail. As we also mentioned above, the data required for such task may be extracted from the available databases or determined using high throughput computational (mostly DFT) and experimental works. ML models built this way are used to correlate molecular descriptors (including electronic and structural properties of material) with desired properties for the model systems like pure substances, single crystals and clean surfaces. Numerous papers, including some reviews, have been recently published in various areas [31]. Similar analysis has been also implemented in catalysis [13,27], including the use of LLMs [32]; however, even though some progress has been made in recent years, difficulties associated with the multicomponent complex structure of catalysts (performing multiple functions unique for specific reactions), appear to be hard to overcome. The performance of a catalyst cannot be completely explained using only the molecular properties of its constituents or the model systems like pure metals, single crystal or perfect surfaces. The macroscopic properties such as surface area, pore size distribution, dispersion of active metal and so on are also highly influential for catalysis. Determining such properties seems to be the most challenging task for ML in catalysis; as there is no single standard (and cannot be) for catalyst synthesis and pretreatment; it is highly difficult to corelate the synthesis and pretreatment parameters conditions with measured macroscopic properties in a quantifiable manner.

Another challenge in catalysis research is the mechanism and kinetics of the reaction. Even if we assume that the change of catalyst material will not affect the mechanism (which is not always true), it will definitely influence the kinetic parameters. Since physical models (like collision and transient state theory) cannot provide quantitative results for real catalysis, and the experimental work for all potential candidates are not practically possible (and often not sufficient due to the neglecting of mass transfer resistances), ML can make significant contribution in this area considering the recent progress in combining the ML with first principle models (physics informed ML). Although there are some work have been performed in the field, the progress is not sufficient yet for any practical purposes [33].

Finally, ML can be used to analyze the actual performance of catalyst and predict the outcome that can be expected in unexplored conditions. Indeed, the ML model relating various catalyst properties and operational conditions with performance measures such as conversion, selectivity and stability have been developed for various catalytic systems by various research groups including ours [13,27]. This type of application is the most common and probably easiest in catalysis research; although it has significant contribution to the understanding of specific catalysis systems, it is still black box in nature and mostly rely very basic features of catalysis and the operational conditions; not directly relating the microscopic and macroscopic properties with performance.

Figure 3. Potential areas for ML contribution to catalysis research

The future

ML tools and applications have been grown remarkably in last two decades, and the recent developments indicates that the progress will be much faster in near future; however, we also have some challenges and difficulties to overcome. In this section we will discuss major developments and potential problems with the perspective of catalysis research

New tools: generative AI and others.

As “the necessity is mother of all innovations”, we can summarize the bottlenecks in the current applications to appreciate the new developments and the potential they possess. One of the biggest critics of ML models is their overreliance of data and neglecting the constraints imposed by physical laws. For instance, how can ML model developed to predict the performance of a catalytic system will know the thermodynamic limits if it was trained by kinetic data only? Furthermore, why should we try to solve our problem with data only if we have laws and equations proven themselves for hundreds of years old? As expected, one of the most significant recent developments in ML applications is hybrid or physics-informed-machine learning approach, which integrates the data and the physical laws in a way that the ML model is forced to satisfy both. Sharma and Liu reviewed the application of hybrid model to chemical engineering problems in two categories as “ML complements science” and “science compliments ML” depending on the weight of data or science. based on the weights of contributions of each side and discussed various models in each category with the chemical engineering examples. [34].

This approach can also help to improve the interpretability and explainability of ML models, which are also criticized as being black-box, together with the other set of recent developments call explainable ML [35].

The transfer learning, which transfers information from a reliable model with large dataset to a similar field with data scarcity, is another new developments[36]; considering the similarity in problems and the processes (like analogies in transport problems; the use of same catalyst in variety of reactions, use of different oxidants to oxidize the same chemical, similarity in mechanisms and rate equations etc.), this line of approaches may progress further in future. There are other developments including new algorithms to handle the small datasets and to identify and focus on rare occurrences and anomalies as well as new better data management tools, better workflow tools that may automate ML for nonexperts and so on. Despite their significance, however, all these developments can be considered as evolutionary changes in the same line of thought compared to the recently introduced generative AI tools, that may represent a revolution in the field.

Generative AI tools, especially large language models (LLM) often associated with GPT (Generative Pre-trained Transformer) or Chat-GPT as generally referred seems to be the most remarkable progress in AI filed in recent years. Although their current applications are mostly limited to writing papers and proposals, carrying out literature surveys or solving students, they will likely have remarkable impacts on research and developments in future as well. As different from the previous tools, these programs have human-like tasks like inference capabilities, create their own contents and do that with an astonishing speed. For example, the number of parameters increased from 1.5 billion to 175 billion from GPT 2 to GPT 3 while it is estimated to exceed one trillion in GPT4 [37]; they can reach waste amount of knowledge with fast connections with web search engines and various calculation tools [38]. Indeed, the number of papers reporting or discussing the applications of LLMs in science and engineering have increased significantly in recent years; while some applications are focusing specific tasks like material synthesis [32], some tests they capabilities comparing with more traditional tools. For example, Guo et al. tested the performance of GPT4 in eight chemistry related tasks: 1) name prediction, 2) property prediction, 3) yield prediction, 4) reaction prediction, 5) retrosynthesis (prediction of reactants from products), 6) text-based molecule design, 7) molecule captioning, and 8) reagents selection; they reported that GPT4 outperformed all other models in most of the tasks with few exceptions [39]. In a similar analysis, Deb et al. showed that ChatGPT can be utilized in the tasks like material discovery, structure−property relationships, materials design and optimization, predictive modeling, material characterization, and literature review and knowledge discovery [40]. The works published in similar nature generally indicate that LLMs are already much better in issues involving textbook level knowledge while they have some errors in less established new research areas; however they will likely be much more efficient in new areas as well considering their fast grow and ability to utilize all kind of resources including those in the form of text, which is still the major storage form of human experience.

Towards field specific databases

As we listed some of them above, significant numbers of experimental or computational databases have been developed in recent years making significant contribution to material research; however, none of them will be sufficient for the discovery and development of new catalytic materials due to the complexity of catalytic process. Most of these databases contain information for pure substance or crystals; in catalysis, however, the data should also contain information to account metal-metal or metal-support interaction and macroscopic properties (pose size distribution, dispersion, surface acidity, surface area and so on), which are highly depend on synthesis conditions and hard to generalize. Most of the catalysts perform unique non-generalizable operational conditions (like temperature, pressure, concentrations, contact time, etc.), which can be determined experimentally. Consequently, the dataset similar to those currently used will not contribute much (except for the initial screening of my materials); a more multi-dimensional approach to dataset is also required, as discussed for the ML tasks in Figure 3.

All-purpose databases are not sufficient in other fields as well as evident from the emergence of field specific data; there are also similar efforts in catalysis in recent years [41-42]. Clearly, this will not be easy considering the nonstandard nature of macro and system-level properties (even if the needs are not standard); however, we can still expect some progress in the form of multiple databases covering multiple aspect of the field or some other data sharing mechanism employing FARE (findability, accessibility, interoperability, and reusability) principles [43].

Challenges and limitations

ML algorithms mostly rely on statistical learning requiring availability of large amount of high-quality data; this is still one of the biggest challenges for ML despite recent improvements in databases and other data sharing options (like open access publication). LLMs do not have a data availability problem; however, the quality of data, especially in the new field, is still a serious concern. Another problem is that there is no standard in testing and reporting the catalysis research results. The problem is much bigger in photocatalysis as our group has some experience in ML applications. For example, the light source used in the experiments are non-standard; the frequency distribution and the intensity of even the same type of light source (for example 300 W xenon light) are different; even the properties of different models of the same brand may differ significantly. The orientation of the light, distance from the reaction medium, the transparent material used in reactors, and properties of reaction medium also influence the light energy absorbed by the photocatalyst [44]. With the addition of other uncertainties arising from the differences in sweep gas flowrate, interfacial surface area between the solid-liquid and liquid-gas phases in dead volume, the situation becomes much worse [45]. Development of standard testing and reporting protocols may reduce this risk as done in some fields.

Ethical and legal concerns about ML (or AI in general) have been also growing in recent years, especially after the emergence of LLMs. For instance, normally, the knowledge extraction from open sources is not unethical or illegal as long as the source is cited properly; the copyright protection is on the artistic creations (drawings and narrative expressions), not on the information content. However, the distinction between the fair use of literature (citing for information and requesting permission for artistic creations) and violating intellectual property rights are not that clear in the use of LLMs because these programs also create their own content (including drawing and textual expressions). Since we do not have much control over the sources used, we may not be sure if some content is partially obtained from another source (belongs to someone else) or created by LLMs (at least intellectually belongs to the created of LLMs). Even if the legal issues are solved, especially for the LLMs created contents, there will still be ethical considerations about the uncertainty for the contributions of researchers and LLMs in designing and executing the research.

Finally, the high cost of building large AI models and infrastructures, which has to be eventually paid by the users, may increase the inequalities among different regions of the world. Even the amount of energy used to run such systems should be taken into account; currently, the data centers are reported to use about 1-1.3 % of world electricity consumption (excluding cryptocurrency mining) and emits about 1 % of energy related GHG emission [46]. These numbers are likely to increase in future creating some concerns while some may argue that these models will have more benefit than their cost; indeed, Tomlinson et al. argued that one-page AI-generated text or image actually consumes less energy than those generated by humans [47].

Conclusion

ML has been used in catalysis research since 1990s; while the initial applications were usually involved the utilization of specific algorithms to in-house generated small sets, more integrated approaches combining multiple algorithms and steps to analyze larger datasets in a well-designed framework has been grown after 2000s. While such line of work is continuing to spread, with more effective algorithms, software codes, data and workflow management tools, generative AI tools emerged as a more revolutionary approach as last few years, and they become instant hits. We can expect that ML/AI tools will be used in research and development including catalysis more extensively and effectively. As the popular saying goes, “data is the new oil”, and we have tools to dig deeper.

References

1. Zupan, J.; Gasteiger, J., Neural networks: A new method for solving chemical problems or just a passing phase? Analytica Chimica Acta 1991, 248 (1), 1-30.

2. Gasteiger, J.; Zupan, J., Neural Networks in Chemistry. Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English 1993, 32 (4), 503-527.

3. Burns, J. A.; Whitesides, G. M., Feed-forward neural networks in chemistry: mathematical systems for classification and pattern recognition. Chemical Reviews 1993, 93 (8), 2583-2601.

4. Himmelblau, D. M., Applications of artificial neural networks in chemical engineering. Korean Journal of Chemical Engineering 2000, 17 (4), 373-392.

5. Mattson, J. S.; Mattson, C. S.; Spencer, M. J.; Spencer, F. W., Classification of petroleum pollutants by linear discriminant function analysis of infrared spectral patterns. Analytical Chemistry 1977, 49 (3), 500-502.

6. Blurock, E. S., Automatic learning of chemical concepts: Research octane number and molecular substructures. Computers & Chemistry 1995, 19 (2), 91-99.

7. Frank, I. E., Modern nonlinear regression methods. Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems 1995, 27 (1), 1-19.

8. Hattori, T.; Kito, S., Neural network as a tool for catalyst development. Catalysis Today 1995, 23 (4), 347-355.

9. Baumes, L. A.; Serna, P.; Corma, A., Merging traditional and high-throughput approaches results in efficient design, synthesis and screening of catalysts for an industrial process. Applied Catalysis A: General 2010, 381 (1-2), 197-208.

10. Arcotumapathy, V.; Siahvashi, A.; Adesina, A. A., A new weighted optimal combination of ANNs for catalyst design and reactor operation: Methane steam reforming studies. AIChE Journal 2012, 58 (8), 2412-2427.

11. Baysal, M.; Günay, M. E.; Yıldırım, R., Decision tree analysis of past publications on catalytic steam reforming to develop heuristics for high performance: A statistical review. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42 (1), 243-254.

12. Şener, A. N.; Günay, M. E.; Leba, A.; Yıldırım, R., Statistical review of dry reforming of methane literature using decision tree and artificial neural network analysis. Catalysis Today 2018, 299, 289-302.

13. Günay, M. E.; Yildirim, R., Knowledge Extraction from Catalysis of the Past: A Case of Selective CO Oxidation over Noble Metal Catalysts between 2000 and 2012. ChemCatChem 2013, 5 (6), 1395-1406.

14. Odabaşı, Ç.; Günay, M. E.; Yıldırım, R., Knowledge extraction for water gas shift reaction over noble metal catalysts from publications in the literature between 2002 and 2012. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2014, 39 (11), 5733-5746.

15. Baroi, C.; Dalai, A. K., Review on Biodiesel Production from Various Feedstocks Using 12-Tungstophosphoric Acid (TPA) as a Solid Acid Catalyst Precursor. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research 2014, 53 (49), 18611-18624.

16. Günay, M. E.; Türker, L.; Tapan, N. A., Decision tree analysis for efficient CO2 utilization in electrochemical systems. Journal of CO2 Utilization 2018, 28, 83-95.

17. Ward, L.; Agrawal, A.; Choudhary, A.; Wolverton, C., A general-purpose machine learning framework for predicting properties of inorganic materials. npj Computational Materials 2016, 2 (1).

18. Bergerhoff, G.; Hundt, R.; Sievers, R.; Brown, I.D. The inorganic crystal structure data base, J. Chem. Inf. Model. 23 (1983) 66-69.

19. Allen, F.H. The Cambridge Structural Database: a quarter of a million crystal structures and rising, Acta Crystallogr., Sect. B: Struct. Sci., Cryst. Eng. Mater. 58 (2002) 380-388.

20. Jain, A.; Hautier, G.; Ong, S.P.; Persson, K.,New opportunities for materials informatics: Resources and data mining techniques for uncovering hidden relationships, J. of Mater. Research 31 (2016) 977-994.

21. NOMAD Repository, https://nomad-repository.eu/, 2019.

22. M. Erdem Günay, R. Yıldırım, Recent advances in knowledge discovery for heterogeneous catalysis using machine learning, Catal. Rev.: Sci. Eng. 2021, 63, 120–164.

23. Alpaydın, E., Introduction to machine learning. 3 ed.; The MIT Press: 2014.

24. Larose, D.T.; Larose, C.D, Discovering Knowledge in Data : An Introduction to Data Mining, second ed., John Wiley & Sons, New Jersey, 2014.

25. Helal, S.,Subgroup Discovery Algorithms: A Survey and Empirical Evaluation, J. Comp. Sci. and Tech. 31 (2016) 561-576.

26. Coşgun, A., Oral, B., Günay, M.E. et al. Machine Learning–Based Analysis of Sustainable Biochar Production Processes. Bioenerg. Res. 17, 2311–2327 (2024)

27. Medford, A. J.; Kunz, M. R.; Ewing, S. M.; Borders, T.; Fushimi, R., Extracting Knowledge from Data through Catalysis Informatics. ACS Catalysis 2018, 8 (8), 7403-7429.

28. Li, H.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Z., Application of Artificial Neural Networks for Catalysis: A Review. Catalysts 2017, 7 (10), 306.

29. Toyao, T.; Maeno, Z.; Takakusagi, S.; Kamachi, T.; Takigawa, I.; Shimizu, K.-i., Machine Learning for Catalysis Informatics: Recent Applications and Prospects. ACS Catalysis 2019, 10 (3), 2260-2297.

30. Goldsmith, B. R.; Esterhuizen, J.; Liu, J.-X.; Bartel, C. J.; Sutton, C., Machine learning for heterogeneous catalyst design and discovery. AIChE Journal 2018, 64 (7), 2311-2323.

31. Cai, J.; Chu, X. Xu, K.; Li, H.; Wei, J., Machine learning-driven new material discovery, Nanoscale Adv. 2020, 2(8), 3115-3130. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1039/D0NA00388C

32. Suvarna, M., Vaucher, A.C., Mitchell, S. et al. Language models and protocol standardization guidelines for accelerating synthesis planning in heterogeneous catalysis. Nat Commun 14, 7964 (2023)

33. Margraf, J.T., Jung, H., Scheurer, C. et al. Exploring catalytic reaction networks with machine learning. Nat Catal 6, 112–121 (2023).

34. Sharma, N, Liu, Y.A, A hybrid science-guided machine learning approach formodeling chemical processes: A review, AIChE J. 2022;68:e17609.

35. Zhong, X., Gallagher, B., Liu, S. et al. Explainable machine learning in materials science. npj Comput Mater 8, 204 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-022-00884-7

36. Li, X.; Dan, Y.; Dong, R.; Cao, Z.; Niu, C.; Song, Y.; Li, S.; Hu, J., Computational Screening of New Perovskite Materials Using Transfer Learning and Deep Learning, Appl. Sci. 2019, 9(24), 5510.

37. Venkatasubramanian, V.; Chakraborty, A., Quo Vadis ChatGPT? From large language models to Large Knowledge Models, Comput. Chem. Eng. 2025, 192, 108895.

38. Hatakeyama-Sato, K., Yamane, N., Igarashi, Y., Nabae, Y., & Hayakawa, T. (2023). Prompt engineering of GPT-4 for chemical research: what can/cannot be done? Science and Technology of Advanced Materials: Methods, 3(1).

39. Guo, T.; Guo, K.; Nan, B.; Liang, Z.; Guo, Z.; Chawla, N. V.; Wiest, O.; Zhang, X., What can Large Language Models do in chemistry? A comprehensive benchmark on eight tasks, arXiv, 2023

40. Deb, J; Saikia, L; Dihingia, K.D.; Sastry, G.N. ChatGPT in the Material Design: Selected Case Studies to Assess the Potential of ChatGPT, J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2024, 64, 3, 799–811.

41. Winther, K.T., Hoffmann, M.J., Boes, J.R. et al. Catalysis-Hub.org, an open electronic structure database for surface reactions. Sci Data 6, 75 (2019).

42. Mendes, P. S. F.; Siradze, S.; Pirro, L.; Thybaut, J. W., Open Data in Catalysis: From Today's Big Picture to the Future of Small Data, ChemCatChem. 2021, 13(3), 836-850.

43. Wilkinson, M., Dumontier, M., Aalbersberg, I. et al. The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Sci Data 3, 160018 (2016).

44. Melchionna, M., Fornasiero, P., Updates on the Roadmap for Photocatalysis, ACS Catal. 2020, 10(10), 5493–5501.

45. Özcan, E. C.; Uner, D;. Yildirim, R, Effects of dead volume and inert sweep gas flow on photocatalytic hydrogen evolution over Pt/TiO2, Int. J. Hydrog. Energy. 2024, 75, 540-546.

46. https://www.iea.org/energy-system/buildings/data-centres-and-data-transmission-networks (Accessed on February 19, 2025)

47. Tomlinson, B.; Black, R. W.; Patterson, D. J.; Torrance, A. W. The carbon emissions of writing and illustrating are lower for AI than for humans, Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 3732.

Solar Energy, Catalysis, and Machine Learning Laboratory

Department of Chemical Engineering

Prepared by Pınar Özdemir, Beyza Yılmaz, Ramazan Yıldırım

Welcome to Yıldırım Research Group 👋👋👋

SolCat & Machine Learning Laboratory operates under the YILDIRIM Research Group at Boğaziçi University Chemical Engineering Department and is a hub for catalysis and photocatalysis research for clean energy development.

Our Aim 🌟🌟🌟We aim to contribute to the development of clean and renewable energy solutions to meet the world's energy needs without causing environmental hazards and climate change.

Research Areas 🌍🔬📖

Various experimental and/or computational research projects in SolCat & Machine Learning Laboratory have been conducted; our research interests include heterogeneous catalysis, photocatalysis, and solar energy utilization for clean energy production like water splitting and photocatalytic carbon dioxide reduction.

We have been also performing machine learning projects in catalysis, photocatalysis and other clean energy areas such as bioenergy and solar energy technologies.

Why Solar Energy and Photocatalysis?

Solar energy is the largest renewable energy resource and the origin of most of the energy forms including wind, wave, hydro, biomass, and ancient fossil fuels. The amount of solar energy reaching the Earth in just one hour is nearly equal to the total annual global energy consumption. Therefore, advancing innovative technologies for solar energy conversion and storage is crucial to address the world's energy challenges.

Photocatalysis offers a promising pathway for harnessing solar energy to drive sustainable chemical reactions, making it a key technology for the future. By utilizing semiconductor materials that absorb sunlight and generate reactive electron-hole pairs, photocatalysis enables efficient solar-to-chemical energy conversion. This process can be applied in hydrogen production through water splitting or biomass reforming, and carbon dioxide reduction for synthetic fuel production while reducing the greenhouse effect.

Why Machine Learning

We have been witnessing a digital revolution that is comparable to but probably more impactful than the industrial revolution. Powerful computers, advanced algorithms and easy access to data in digital storage systems allowed us to obtain massive amounts of data and analyze it using machine learning/artificial intelligence (ML/AI) tools for knowledge extraction. We seem to enter in a new phase of digital change with the recent emergence of generative AI tools, which have the capacity to utilize waste amount of knowledge, capability to perform human like inference tasks and establish fast connections with web search engines and various calculation tools. These tools appear to have significant potential to contribute to the discovery and development of new materials, including catalysts, photocatalyst and other energy materials.

State-of-the-Art Laboratory Infrastructure ⚙️🖥️📟

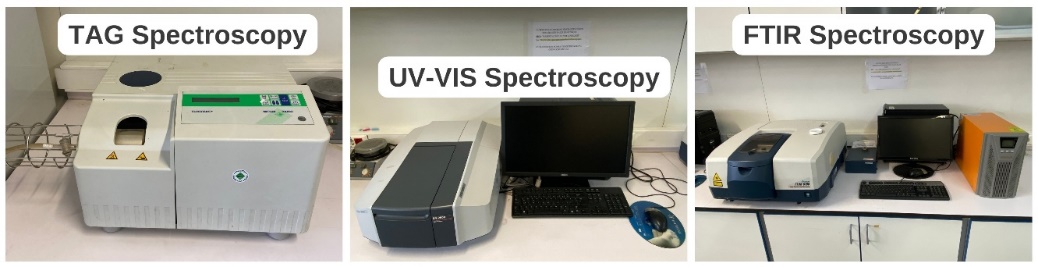

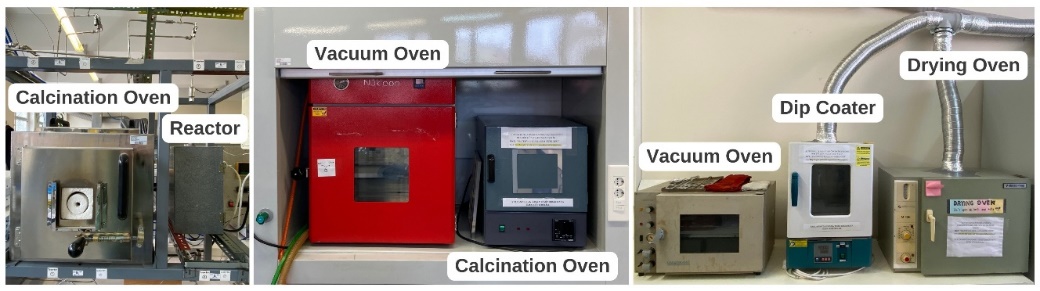

The photocatalytic reaction tests were performed in photoreactors equipped with suitable lamps; the amount of hydrogen produced was measured via Gas Chromatography. In addition, photoelectrochemical water splitting was also studied to produce hydrogen by varying preparation methods of photoelectrodes, metal doping, pH, and molarity of electrolytes; the Linear Sweep Voltammetry method was applied to compare the photoelectrochemical performances of the tested cells. For catalyst characterization, researchers benefit from available FTIR, UV-VIS, XRD, and SEM analyses which are in our laboratory and university.

As for our laboratory’s equipment enables fundamental and applied studies. Some of our key instruments include:

In-Situ Photocatalytic CO2 Reduction Systems

For real-time reaction monitoring and analysis of reaction products and catalyst efficiency.

TAG/UV-VIS/FTIR Spectroscopies

For the characterization of prepared samples.

Reactor/Oven/Dip Coater Systems

To conduct reactions into different gas combinations, calcination, and drying processes.

Glovebox and Dark Room

To create proper conditions for no air applications (glovebox) and light-sensitive material synthesis (dark room).

Publications ✏️ ✏️ ✏️

Under the umbrella of SolCat & Machine Learning Laboratory, we published over 80 research/review articles, which can be found on our LinkedIn page (linkedin.com/in/ramazan-yıldırım-solcatml405) and in our posts on our research group's website (yildirim.che.bogazici.edu.tr/).

https://doi.org/10.1021/acscombsci.8b00150 -- https://doi.org/10.1002/ente.202270031

Collaborations & Projects 👥🔗👥

We also collaborate with other groups in our department and other universities to extend our research, especially machine learning applications, into energy-related fields such as biofuels, lithium batteries, MOFs, desalination, and solar cell applications.

Participations in conferences and Summer Schools 🚀🚀🚀

Our lab allows graduate and undergraduate students to engage in high-level research projects, developing expertise in experimental and computational catalysis. We also participate Workshops & Seminars & National and International Conferences & Summer Schools

As the SolCat & Machine Learning Laboratory research team tries to communicate our research, and projects in various social settings including national and international conferences, we also share our datasets with other researchers, who want to conduct machine learning research in the same fields.

Reach out to us!

SOLCAT: yildirim.che.boun.edu.tr

Linked-in: www.linkedin.com/in/ramazan-yıldırım-solcatml405

E-mail: yildirra@bogazici.edu.tr

Address: Boğaziçi University, Department of Chemical Engineering, Istanbul, Turkey

PhD Stories

I am Orhan Özcan. I received my Ph.D. from the Department of Chemical Engineering at Kocaeli University in 2023. Between 2012 and 2025, I worked as a research assistant in the same department, and as of February 2025, I continue my academic career as an Assistant Professor. My doctoral dissertation focused on hydrogen production from methanol, catalyst development, and kinetic studies. Throughout this challenging journey, I am profoundly grateful to my advisor, Prof. Dr. A. Nilgün Akın, for her guidance and support.

When I decided to pursue a doctorate after completing my master’s degree, Prof. Nilgün Akın asked me, “Are you sure? 😊” With great confidence, I responded, “Yes” Of course, at that moment, I did not fully grasp to what I was committing. However, the fulfillment of pursuing my dream profession outweighed all the difficulties I encountered. That being said, I am not counting the times I stormed out of the lab after a failed experiment or the moment I accidentally dropped a catalyst I had spent days preparing.

One of my greatest sources of support during this journey was, as always, my dear wife, Merve Doğan Özcan. We conducted our doctoral research in the same laboratory. Part of our research was with the pandemic restrictions, during which we had our mealtime soup from disposable cups in the lab—an experience I do not particularly miss, though the experiences were unforgettable.

One of the most unforgettable moments of my doctoral studies was the unexpected results—or lack thereof—during preliminary experiments for a planned study. This phase consumed more than a year of my time, and just when I was on the verge of concluding the study with frustration, I thought, “What if I try this one last thing?” The results I obtained that day reinvigorated my motivation (and, though I won’t admit it, might have brought tears to my eyes). Even now, I occasionally revisit my final paper on ScienceDirect.

The doctoral process was not solely defined by academic struggles; it also brought numerous enriching experiences. From lab pizza parties to the excitement of designing and executing experiments, from managing research projects and awaiting grant approvals to attending conferences and symposiums where I had the privilege of meeting esteemed professors in my field—each moment was invaluable. Beyond expanding my scientific knowledge, this journey taught me perseverance, resilience, and the significance of collaboration.

My future career goal is to prepare for the associate professorship process with ever-growing motivation and to continue my academic journey without pause— “Acta non verba.”

Recent Selected Papers in Our Catalysis Community

In recent months, there have been exciting research studies in catalysis research in Turkey. Here are the short summaries:

Photocatalysis

Görener, E., Tuna, Ö., Fırtına Ertis, İ., Bilgin Simsek, E. (2025). Design of novel Z-scheme Ce2(WO4)3 heterostructure using tubular g-C3N4 for boosted photocatalytic performance via effective electron transfer pathway. Journal of Molecular Structure, 1323,140736.

This study introduces a novel Z-scheme heterostructure catalyst composed of tubular graphitic carbon nitride and cerium tungstate, synthesized via an ultrasonic-assisted thermal impregnation method. Comprehensive material characterization demonstrated that the hybrid catalyst exhibited significantly enhanced photocatalytic activity, achieving a kinetic rate constant 3.4 times higher than that of pristine cerium tungstate for the degradation of tetracycline under visible light irradiation. The superior performance of the hybrid catalyst was attributed to its increased surface area, reduced band gap energy, and the formation of a Z-scheme heterojunction mechanism.

Büyüker Tan, F., Karadirek, Ş., Tuna, Ö., Bilgin Simsek, E. (2025). Anchoring of tungsten on g-C3N4 layers towards efficient photocatalytic degradation of sulfadiazine via peroxymonosulfate activation. Diamond & Related Materials, 152,111939.

This study enhanced the catalytic efficiency of graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4) by doping it with tungstate (W) through a simple calcination method, resulting in the formation of oxygen vacancies, a narrowed band gap, improved light absorption, and reduced recombination of photoactive species. In the visible light (Vis)/PMS process, the W-doped g-C3N4 (W-CN@3) significantly increased the degradation efficiency of sulfadiazine (SDZ) from 27.9% to 81.2%, demonstrating optimal performance at neutral pH with increased catalyst dosage and PMS concentration. The removal system was primarily driven by superoxide and sulfate radicals, with additional contributions from hydroxyl radicals and photoinduced holes, highlighting the potential of W-doped g-C3N4 for effective antibiotic degradation under visible light irradiation.

Nejatpour, M., Ünsür, A.M., Yılmaz, B., Gül, M., Ozden, B., Barisci, S., Dükkancı, M. (2025). Enhanced photodegradation of perfluorocarboxylic acids (PFCAs) using carbon quantum dots (CQDs) doped TiO2 photocatalysts: A comparative study between exfoliated graphite and mussel shell-derived CQDs. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering, 13, 115382.

This study investigates the photodegradation of perfluorocarboxylic acids (PFCAs) using carbon quantum dot (CQD)-doped TiO₂ composites, addressing the environmental impact of these persistent pollutants. CQDs were synthesized through electrochemical exfoliation of graphite rods and a hydrothermal process using mussel shell biomass, with the Exfol.CQD/TiO₂ composite showing superior performance, doubling PFOA degradation under visible light and achieving 22–40% degradation for short-chain PFCAs. The findings demonstrate the potential of CQD/TiO₂ composites for efficient PFCA removal in wastewater treatment, though further optimization is needed for the MCQD/TiO₂ variant.

Hydrogen Production

Öner Akduman, H., Özdemir, E. (2025). Zirconia supported bimetallic Co–Mn–B catalyst with superior catalytic activity for hydrolysis of sodium borohydride. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 100, 67–78.

This study presents an efficient, reusable, and cost-effective Co–Mn–B catalyst supported on ZrO2 for hydrogen production from sodium borohydride. The catalyst achieved a maximum hydrogen generation rate of 10.40 ± 0.8 L/min‧gmetal at 30°C, with an apparent activation energy of 43.68 kJ/mol, and improved NaBH4 utilization efficiency from 89.0% to 96.2%. Notably, the catalyst retained 73% of its activity after five cycles, with its enhanced performance attributed to a nanoflower surface morphology that prevented cobalt agglomeration and deactivation.

Waste Valorization

Örtün, H., Sert, M., Sert, E. (2025). Utilization of spent coffee ground and mussel shell as heterogeneous catalyst for sustainable glycerol carbonate synthesis. Biomass and Bioenergy, 194, 107624.

This study used biochar from spent coffee grounds (SCG) as a heterogeneous catalyst for glycerol carbonate production, with biochar obtained at 600°C (C600) showing the highest catalytic activity. Incorporating CaO from waste mussel shells (MS) into the biochar (C600MS) increased basic sites and catalytic performance, achieving 58.5% conversion and 84.9% selectivity under optimal conditions. This work demonstrates a cost-effective and sustainable approach to converting waste materials into efficient catalysts for glycerol carbonate production.

Gas Separation

Gulbalkan, H.C., Uzun, A., Keskin, S. (2025). Assessing CO2 separation performances of IL/ZIF-8 composites using molecular features of ILs. Carbon Capture Science & Technology 14, 100373.

This study developed a comprehensive computational approach combining COSMO-RS, DFT, GCMC simulations, and machine learning to evaluate IL-incorporated ZIF-8 composites for CO2 separation. By examining 1322 IL/ZIF-8 combinations with various cations and anions, the team simulated gas adsorption properties and built ML models to predict gas uptake based on IL chemical and structural features. This method accelerates the screening process and identifies key IL characteristics for superior gas separation performance.

Reaction Mechanisms and Kinetics

Atman, B., Karakaş, G., Uludağ. (2025). Mathematical modeling of response dynamics of n-type SnO2-based thick film gas sensor. Materials Science in Semiconductor Processing, 190, 109360.

This study developed a detailed mathematical model to describe the complex sensing mechanism of semiconductor metal oxide (SMOX) gas sensors, considering mass transfer, surface reactions, electron transfer, and electric current flow. The model was tested on n-type SnO2 thick film sensors exposed to CO gas in dry air, analyzing factors like temperature, film thickness, and pore size affect surface reduction/oxidation and diffusion rates. Simulation results were validated against experimental data for different CO concentrations at 528K, showing strong agreement with observed sensor responses.

Methane Reforming

Ay, H., Mao, H., Xu, J., Reimer, J.A., Uner, D. (2025). Tracking the Mode of Carbon Deposition During Dry Reforming of Methane over Ni/γ-Al2O3. ChemCatChem, e202401856.

This study investigated dry reforming of methane over a Ni/Al2O3 catalyst at 600°C with varying CO2/CH4 ratios, using isotopic labeling and 13C NMR to track carbon deposition. Results showed that carbon buildup came from both CH4 and CO2, with a critical CO2/CH4 ratio of 1.8 needed to inhibit significant carbon growth. Above this ratio, only small amounts of amorphous carbon formed, while below it, whisker-like carbon structures developed though transient CO2 injection reduced coke deposition at the cost of hydrogen stoichiometry.

Previous issue answers Newsletter #11:

1. Suzuki, 2. Ibuprofen, 3. Azobenzene, 4. Gaussian, 5. ORCA, 6. DFT, 7. Cluster, 8. Safety

Announcements

In 2025, there will be a highly active program of events in the field of catalysis.

• From June 25 to 28, 10th National Catalysis Conference (NCC10), organized by the Catalysis Society and Cumhuriyet University, will take place in Sivas. We look forward to welcoming you there.

• From July 9 to 11, The 14th International Symposium of the Romanian Catalysis Society (RomCat 2025), organized by Societatea De Cataliza Din Romania will be held on Gluj-Napoca, Romania. For more information: http://www.unibuc.ro/romcat/

• From August 31 to September 5, 16th Europacat Conference, organized by EFCATS, of which our society is a member, will be held in Trondheim, Norway.

• From September 1 to 4, 36th National Chemistry Congress, organized by Van Yüzüncü Yıl University will feature a "Catalysis" session supported by Catalysis society."

• From September 9 to 12, the 16th National Chemical Engineering Congress, organized by Bolu Abant İzzet Baysal University, will host a special session on "Catalysis and Reaction Engineering," supported by Catalysis society.